By Courtney McAllister

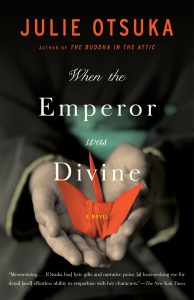

In When the Emperor Was Divine, Julie Otsuka uses a sparse, lyrical writing style to illuminate the psychological effects of one of the most shameful episodes in U.S. history. The novel opens with a portrait of an ordinary woman going about her daily chores in Berkeley, California. While en route to her local library, she sees something troubling: Evacuation Order No. 19. After reading the notice, she abandons her errands and begins preparing for life in an unfamiliar locale.

At first, the sequence of events feels dystopian or apocalyptic – the world is ending and a family is forced to prepare to face the unknown. But this narrative is a dramatization of history, not a speculative tale of the future. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, the U.S. government began to suspect that American citizens of Japanese ancestry might harbor allegiance to Japan. In 1942, these paranoid fantasies lead to the forcible internment of Japanese-Americans announced in Evacuation Order No. 19.

When the Emperor Was Divine follows one family’s experience of exodus, exile, and the aftereffects of being labeled an “enemy alien.” Otsuka withholds the names of the mother, father, and their two children, referring to them only by pronouns and generic terms like woman, man, boy, and girl. At times, it was frustrating not to have more personal information about the main characters, but I suspect Otsuka deliberately avoided giving the characters concrete identity markers. Denying them names parallels how their identities were stripped away during internment. In the camps, they were known by identification number, not by name. The absence of names also gives the man, woman, boy, and girl metonymic qualities. On one level, their experiences are representative of a larger collective trauma, not just personal crises. Regardless of Otsuka’s motives, the lack of character names does not diminish the novel’s emotional resonance and power.

Much of When the Emperor Was Divine revolves around an absent figure: the man/father. Months before the Evacuation Order was posted, he was taken and detained for “questioning.” The children obsessively recall the circumstances of his late-night abduction. Their memories are anything but comforting, however, and the heavily-censored postcards and letters they get from their father are disturbingly vague on the topic of his fate.

During the three years and five months, the mother and her two children spend in captivity, they are in limbo, never knowing when they’ll be released or what will happen to them if the United States doesn’t win the war. The son sees phantom images of his father everywhere, like a perpetual mirage, while the mother clings to the key to their home in Berkeley, treating it like a talisman that will guarantee their safe return home.

Eventually, the war ends, and the woman, the boy, and the girl are allowed to leave the internment camp. When they arrive back at Berkeley, they discover that many things have changed during their absence. The woman bravely tries to restore order, but the memories of the camp are not easily forgotten. It seems as though only the father’s return can help the family reclaim a sense of normalcy. The woman and her children assume his presence will magically transform them into the family unit they were in a more idyllic time. But their reunion only reveals the intractable fissures created by the trauma they have each experienced.

Julie Otsuka’s other novel, The Buddha in the Attic, can be read as a sort of prequel to When the Emperor Was Divine. It follows a group of women who emigrate from Japan to the United States as “picture brides.” The novel explores the physical, cultural, and psychological aspects of their struggle to assimilate and adapt to life in the United States. After spending decades living in their adopted homeland, they are forced to abandon their homes and leave for the same camps which are described in When the Emperor Was Divine. Joy Kogawa’s Obasan is another excellent fictionalized account of internment. When the Emperor Was Divine, it eschews melodrama in favor of raw, visceral depictions.