Westmoreland County’s African American history dates back to the 17th century. During the earliest years, both enslaved people from Africa and white indentured servants were imported to the Northern Neck (the land between the Potomac and Rappahannock rivers) to work on farms and plantations, with enslaved Africans becoming more prevalent over time.

17th Century – The Beginning and a Rebellion

The first enslaved Africans were imported to the Virginia colony in 1619. Their numbers were few at first, but, by 1681, opens a new window, about 3,000 enslaved Africans worked alongside approximately 15,000 white indentured servants, opens a new window. On October 24, 1687, Royal Governor’s Councilor Colonel Nicholas Spencer, opens a new window reported a plot by enslaved Africans and enslaved African Americans in Westmoreland County to kill the white colonists and destroy their property, not only in the county but throughout Virginia. The Westmoreland Slave Plot, opens a new window was the first conspiracy in British North America to not involve white colonists or American Indians. Spencer captured the accused enslaved Africans and African Americans (“some of the Principall Actors & Contrivers”) before the plot could come off and delivered them to the governor, who created a special commission to try the suspected rebels. The commission included their accuser, Nicholas Spencer. A London merchant turned colonial man-of-importance and major holder of enslaved persons, Nicholas Spencer's friends included John Washington, opens a new window, George Washington's ancestor, and he helped survey the Washington estate on the banks of the Potomac that became Mount Vernon. Spencer recorded his purely mercantile thoughts on slavery: "The low price of Tobacco," Spencer wrote, opens a new window, "requires it should bee made as cheap as possible, and that Blacks can make it cheaper than Whites." With a profit motive foremost in mind, the importation of enslaved Africans continued through the next century and beyond.

No records exist of the 1687 trial’s proceedings or its outcome, but similar commissions would be created for later Virginia slavery rebellions, and this 1687 rebellion was used as justification for tightening "slave laws", opens a new window and sharpening penalties for disobedience. But the rebellions would continue. The following year, in April of 1688, an enslaved African American named Sam, opens a new window - owned by a Westmoreland County planter name Metcalfe - was found guilty, along with his co-conspirators, of fomenting rebellion. He was not hanged, but whipped in two localities and made to wear a heavy collar around his neck for the rest of his life.

18th Century – Plantations, “Free Blacks,” Revolution, and Jubilee at Nomini Hall

Alongside the pervasive backdrop of slavery, there also lived families of “free blacks.” These people may have held their freedom for generations, having had ancestors or ancestresses who either bought their freedom through outside wages earned or who had it granted to them by their owners. Though still denied certain freedoms and education by “black laws,”, opens a new window they made their own places in the community. These "free black" men were among those who served in the American Revolution: Bennett McCoy (Kinsale), James McCoy (Kinsale), and Rodham McCoy (Westmoreland County). These four free Westmoreland County men are recorded as receiving pensions: Thomas Mahorney, Joshua Payne, Thomas Sorrell, and Nathan Fry. Enslaved African Americans also served in the Revolution. Born in Westmoreland County on a Lee estate, William "Billy" Lee accompanied General George Washington, and his likeness, opens a new window can be found in several wartime portraits depicting Washington. Lee was the only enslaved African American freed outright by Washington in his will.

African Americans living in Westmoreland County contributed to the building of the new capital in Washington. For example, in 1792, opens a new window, a nephew of George Washington was advised to hire "twelve good Negro carpenters and ten Axe-men" to clear a tract in Westmoreland County’s White Oak Swamp for timber.

At the end of the 18th century, one of the wealthiest men in Virginia – Robert Carter III – made the then unpopular decision to free his enslaved African Americans. The records of many of the people Carter freed and resettled on lands he gave them still exist, opens a new window, and that dramatic act of conscience is still celebrated, opens a new window in the 21st century. His original home, Nomini Hall, no longer stands, having burned down in the mid-19th century, but it has been rebuilt as a frame structure., opens a new window Ironically the lands at Nomini Creek once belonged to aforementioned Royal Councilor Nicholas Spencer.

19th Century – The End of Slavery and What Came After

Unrest continued into a new century. In 1809, rumors spread among Westmoreland's white community that a general insurrection was planned for Christmas Eve. Cabins throughout the county were searched, and an enslaved African American named Joe was mortally wounded when he tried to flee. This matter came before a court – which is why we have a record, opens a new window of it – when his "owner" tried to claim compensation.

In the years leading up to the Civil War and shortly thereafter, men and women who had lived through slavery times told their stories, which served as fuel for the abolitionist movement. From Still's Underground Rail Road Records, opens a new window (1886):

STAFFORD SMITH fled from Westmoreland County, Virginia, where he was owned by Harriet Parker, a single woman, advanced in years, and the owner of many slaves. "As a mistress, she was very hard. I have been hired to first one and then another, bad man all along. My mistress was a Methodist, but she seemed to know nothing about goodness. She was not in the habit of allowing slaves any chance at all.”

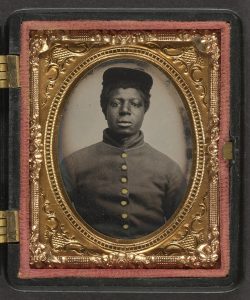

The war itself brought opportunities for freedom even as enslaved African Americans were pressed into work for their masters’ cause. Samuel Ballton,* born on the Marmaduke plantation, adjacent to Stratford, in Westmoreland County, was one of many enslaved African Americans initially sent to work on the railroad for the Confederacy, miles from home in the Blue Ridge Mountains. With four companions, he ultimately made a break for freedom, eventually joining up with the Union Army's Sixth Wisconsin as a cook. When the opportunity presented itself, he made his way back into Confederate territory and helped his wife escape, and they made their way through Fredericksburg to Alexandria. Within two years, he enlisted with the Fifth Massachusetts Cavalry of the U.S. Colored Troops. After the war, he and his wife settled in Long Island where he became a prosperous farmer and business owner. Samuel Ballton was not alone in joining the Union Army. There were 34 African American men from Westmoreland County who joined Union forces.

Many now free African Americans stayed in Westmoreland County. They made their livings by opening shops and stores, farming land both their own and as tenants, working at crafts and trades and fishing, opens a new window the nearby waters for oysters, crabs, and more. Working as a community with enduring family ties, they built and led their own churches and took care of each other in the years following the Civil War.

African Americans from Westmoreland County continued to serve in the U.S. armed forces after the Civil War, including Walter Tate, James Arthur Dean, and Richard Johnson, opens a new window who saw activity in the U.S. Cavalry as “Buffalo Soldiers”, opens a new window in the West.

20th Century – Progress and Remembrance

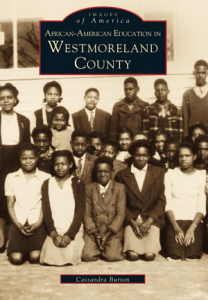

Making education available to African Americans was a crucial post-war change, as educating African Americans - enslaved or free - had been a criminal offense. That ended with the Civil War, but, in 1870, statistics showed African American illiteracy at 79.9% while white illiteracy was at 50%. A change was in order across the board, and William H. Ruffner, the first state school superintendent, wrote an act that provided free education (albeit segregated) for students regardless of color. Numerous small African American schools sprang up around the county. According to Cassandra Burton's African-American Education in Westmoreland County, opens a new window, in the immediate aftermath of the War, an African American church might be used as a schoolhouse during the week, and the churches held fundraisers to support their students and teachers. Two wealthy Northern industrialists - George Peabody and John F. Slater - created educational funds that would help fund Westmoreland County's African American schools. Notably, The Slater Fund for the Education of Freed Men, opens a new window was used to help build the A.T. Johnson High School in 1937. Armstead Tasker Johnson (1857-1944) was an African American educator and community leader of the grass-roots effort for its construction. The school's faculty was integrated in the 1960s, and it admitted its first non-African American students in the 1970s. In 1998, it closed its doors as an operating school, but it now functions as a museum.

Making education available to African Americans was a crucial post-war change, as educating African Americans - enslaved or free - had been a criminal offense. That ended with the Civil War, but, in 1870, statistics showed African American illiteracy at 79.9% while white illiteracy was at 50%. A change was in order across the board, and William H. Ruffner, the first state school superintendent, wrote an act that provided free education (albeit segregated) for students regardless of color. Numerous small African American schools sprang up around the county. According to Cassandra Burton's African-American Education in Westmoreland County, opens a new window, in the immediate aftermath of the War, an African American church might be used as a schoolhouse during the week, and the churches held fundraisers to support their students and teachers. Two wealthy Northern industrialists - George Peabody and John F. Slater - created educational funds that would help fund Westmoreland County's African American schools. Notably, The Slater Fund for the Education of Freed Men, opens a new window was used to help build the A.T. Johnson High School in 1937. Armstead Tasker Johnson (1857-1944) was an African American educator and community leader of the grass-roots effort for its construction. The school's faculty was integrated in the 1960s, and it admitted its first non-African American students in the 1970s. In 1998, it closed its doors as an operating school, but it now functions as a museum.

In recent years, some of Westmoreland County's local historians have been keeping the flame of the past alive as Westmoreland Weavers of the Word, opens a new window, a storytelling group that focuses on African American history and customs. Their stories can be heard during special events at museums and libraries in our region.

Learning More

These local museums and historic sites have information that is of interest to those studying African American history:

Armstead Tasker Johnson High School Museum, opens a new window (18849 Kings Highway, Montross) - Established to preserve the history and legacy of education for African American students in the Northern Neck of Virginia, especially in Westmoreland County, and to make the information readily available to the public. The museum is a depository of collections, artifacts, memorabilia, documents, and other items related to education in the area. The A.T. Johnson High School, for which the museum takes its name, is named after Armstead Tasker Johnson, a prominent African American educator and leader in the community.

The Museum at Colonial Beach, opens a new window – includes its Watermen’s Room, a permanent exhibit that looks at aspects of that shared heritage. Colonial Beach was an extremely popular tourist destination during the earlier part of the 20th century. The museum is open to visitors from early April until mid-December.

If you visit Popes Creek Plantation (George Washington’s Birthplace National Monument, opens a new window), you may encounter African American guides who specialize in “living history” and can demonstrate daily life on the plantation, including cooking, working with animals, farming, blacksmithing, and other folkways.

The research library at historic Stratford Hall, opens a new window has information the Payne Family, opens a new window, who are believed to be descended from enslaved African Americans who lived on the plantation. Stratford Hall often hosts events which touch on aspects of African American history, such as the "Forum on Racial Understanding: Finding Stratford’s Enslaved Stories.”

*Thomas, William G. "Been Workin’ on the Railroad."

New York Times (Online), New York: New York Times Company. Feb 10, 2012.

CRRL cardholders can access the post through our New York Times Newspaper database, opens a new window and searching for "Samuel Ballton".

Library Resources

African-American Education in Westmoreland County, opens a new window by Cassandra Burton

African American Military - Westmoreland County, Virginia, opens a new window by Daisy Howard-Douglas

Black America Series: Westmoreland County, opens a new window by Cassandra Burton

The Descendants of the First Mitchell Wilson of Westmoreland County, Virginia - 1824 to 2002, opens a new window by Daisy Howard-Douglas

The Descendants of Sallie Elizabeth Crabbe of Westmoreland County, Virginia, 1830 - 2013, opens a new window by Daisy Howard-Douglas

Online Genealogy Resources

FamilySearch – Westmoreland County, VA Genealogy – African American, opens a new window

Nomini Hall Slave Legacy Project, opens a new window

Virginia Untold: The African American Narrative, opens a new window

Westmoreland County (Va.) Free Negro and Slave Records, 1780-1863, opens a new window