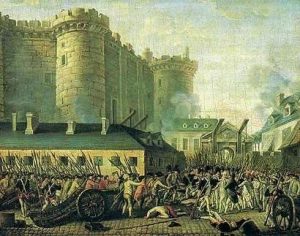

On July 14, 1789, a Parisian mob broke down the gates of the ancient fortress known as the Bastille, marking a flashpoint at the beginning of the French Revolution.

"What is the third estate? Everything. What has it been up till now in the political order? Nothing. What does it desire to be? Something."

- Emmanuel Joseph Sieyes, French political activist

For years, the anger between the three major social classes, called Estates, had grown to a fever pitch. The First Estate was the clergy. The Second Estate was the nobility. The Third Estate was everyone else - the poor, the shopkeepers, and the middle classes. It was by far the largest group of people, and quite a number of them were well-educated clerks, lawyers, teachers, and so on.

The philosophical ideas of Cicero, opens a new window and Rousseau, opens a new window fueled the Revolutionary fire. In old Rome, Cicero had promoted the restoration of original Republican values to a state whose nobility seemed cheerfully mired in decadence and corruption.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who died a short time before the French Revolution, argued for a civil society that would be voluntarily formed by its citizens and wholly governed by reference to their general will. Citizens governed in this way, he believed, would unanimously accept their governing authority.

Rousseau proposed that man in his natural state, without the interference of defective laws, was a "noble savage" whose natural desire was for simple justice. Members of the Third Estate found many examples of laws created simply to enrich the nobility.

The nobles of the Second Estate were not entirely happy with the situation, either. They wanted to curtail the King's right to exercise his power, which the royal family believed to come directly from God, hence the expression "the Divine Right of Kings."

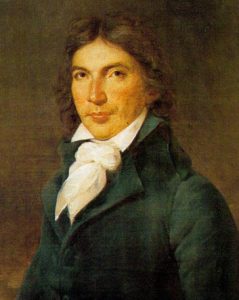

On June 17, 1789, the Third Estate, frustrated in its attempts to reform the political order, decided to break from the Estates General and form a new "National Assembly." On June 20, 1789, the organizers found themselves locked out of their regular meeting place, so they gathered at a nearby tennis court and swore what would become known as the Tennis Court Oath, that they would continue to meet until they had established a new constitution for France. In the days leading up to the fall of the Bastille, fiery orators stood on street corners calling the crowds to action, including Camille Desmoulins, opens a new window.

To the French people, the Bastille represented the corrupt power of the nobility. Here, political prisoners, as well as ordinary criminals, were left to rot, although it is true that those who had money, such as the Marquis de Sade, could buy a more comfortable existence. At the time of the fall of the Bastille, there were only seven prisoners released from its chambers, but its destruction nevertheless became a symbol of the end of King Louis XVI's power to quash the rising tide of the Third Estate.

The bloody aftermath of July 14 was fueled by generations of rage against the status quo and new leaders from the middle class, idealistic and otherwise, who jockeyed for power. Trials became mockeries of justice, and some of the Revolution's early leaders died without defense on the blade of the guillotine.

Desmoulins met that fate, as did one of the creators of its feared military tribunal, Georges Jacques Danton, opens a new window. The famed French scientist Antoine Lavoisier, opens a new window, known as the father of modern chemistry, also perished in the public square, as did countless other men and women who had been declared enemies of the state.

Curious to learn more about the French Revolution? The library and the Web have sources to aid you in your discovery. These are just a few of the possibilities.

Ideals, Politics, and Leaders

Fatal Purity, opens a new window

The French Revolution, opens a new window

The French Revolution: From Enlightenment to Tyranny, opens a new window

Two Classics of the French Revolution, opens a new window

Fiction

A Dish Taken Cold, opens a new window

Scaramouche, opens a new window

The Scarlet Pimpernel, opens a new window

A Tale of Two Cities, opens a new window

Where the Light Falls, opens a new window

Other Aspects

The Lady and the Duke, opens a new window

Rebellious Hearts, opens a new window

Websites

Catholic Encyclopedia: French Revolution, opens a new window

This page details the experience of the First Estate, the clergy, during the Revolution, when Catholicism ceased to be the religion of the State in France.

Liberty, Equality, Fraternity: Exploring the French Revolution, opens a new window

This rich site from George Mason University has essays, images, maps, songs, a timeline, and a glossary to make studying the time period a pleasure. Includes materials on Napoleon.

The Marquis de Lafayette and Two Keys to the Bastille, opens a new window

There are local connections to Bastille Day. The French patriot and hero of the American Revolution sent his friend George Washington a key to the Bastille in 1790 as a symbol of freedom and the overthrow of oppression. This artifact is now on display at Mount Vernon. During Lafayette's 1824-25 American tour, he presented another larger key to Bastille to the Alexandria-Washington Lodge No. 22. That key may now be seen at the Museum of the George Washington Masonic National Memorial in Alexandria, Virginia.

Place de la Bastille, Paris, opens a new window

Read a quick history of the French landmark and learn its role in Paris today.