By Chuck Gray, John Gaines, and Craig Graziano

Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery. Isn’t that how an article about derivative works is supposed to begin? We only ask because there are probably other articles out there on this topic that begin the same way. Whether or not we admit it to ourselves, 100% true originality in the case of media such as books, film, music, and games is practically unheard of. That’s not a bad thing; works that build on one another can be some of the richest experiences imaginable. On the other hand, some people are just lazy and rip off other, greater works. Whatever the case, the world of derivative works is a fascinating one, tracing the path from modern works to their roots in the past or even the present.

Let’s start with books. Book derivations are the stuff of legend. A goodly-sized chunk of the books we consume is genre fiction. Mystery, romance, sci-fi, fantasy, westerns, etc.—there’s little there that wasn’t inspired by both earlier and contemporary works. One of the greatest and most prolific mystery writers of the latter 20th century, the late Robert B. Parker, drew heavily from Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe for all three of his main characters, specifically, Spencer, Jesse Stone, and Sunny Randall. All three of Parker’s creations were inspired by Marlowe’s wisecracking, tough-guy, heart-of-gold archetype, which, in turn, grew out of the early 20th-century hard-boiled mystery genre that introduced other detective greats like Sam Spade.

J. R .R. Tolkien, author of The Lord of the Rings trilogy, surpasses the influential force of Raymond Chandler and has practically defined the fantasy genre. Myriad creatures, such as elves, dwarves, orcs, dragons, and demons set in vaguely medieval British environs, have Tolkien to thank for their popularity. So much of fantasy, from Robert Jordan’s lengthy Wheel of Time series to the hugely popular online role-playing game World of Warcraft feed off of the mythos that Tolkien brought to life.

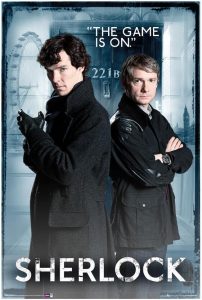

And let us speak, naturally, of Sherlock Holmes. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's famous creation has been resurrected countless times in print and film, most recently by Guy Ritchie and Robert Downey Jr. and the BBC series Sherlock, a modern-day take on the eccentric genius. But what has always been fascinating is watching Holmes and Watson recreated in the characters Greg House and James Wilson in the hit Fox TV show, House M.D. It’s great fun observing the banter between Hugh Laurie and Robert Sean Leonard in a modern context and then observing that same behavior between RDJ and Jude Law in their original, albeit more steampunk, setting.

Many authors in the last decade have been taking advantage of the public domain to remix classic works of fiction into bizarre tales with more modern sensibilities. Books in the Quirk Classics series, such as Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, Sense and Sensibility and Sea Monsters, and Android Karenina are wonderful examples of how works in the public domain can benefit creativity.

It’s not always works of fiction whose pages find their way into another’s work. Dan Brown’s 2003 international bestseller, The Da Vinci Code borrowed heavily from the ostensible non-fiction 1982 book Holy Blood, Holy Grail, by Michael Baigent, Richard Leigh, and Henry Lincoln, with Brown even going so far as to name one of his characters after the first two authors. The authors took Brown to court alleging plagiarism, but the case was dismissed.

Of course, we’re talking about books influencing one another here, but there are many instances in which writers find themselves the victims of all-out piracy. Author J.K. Rowling’s works live on in a series of knock-offs that are famously popular in China. An investigator quoted in the linked New York Times article suggests that as many as 30 to 40 percent of books sold in China might be illegal.

For a long time, truly derivative films were typically very low budget and given sparse theatrical releases, making them available to only a small audience. The few times when a derivative film got a mass release proved very controversial, as shown when Universal successfully sued the makers of the Italian Jaws ripoff Great White and prevented it from ever seeing a U.S. theatrical release (although it would later resurface as a Rifftrax download over three decades later!). As long as theatrical viewing was the primary means of viewing films, the number of movies that could be distributed and shown in the system was limited, restricting the possibility that low-budget ripoffs of popular films would be available to a wide audience.

Over the 1990s and 2000s, however, theatrical moviegoing diminished, and home viewing became more popular, allowing many makers of low-budget films to distribute their films in Blockbuster stores, Redbox kiosks, and online services such Hulu and Netflix. One of the genres that produced the most derivative films was children’s animation—it was not uncommon back in the 1990s to see movies with titles such as Hercules and The Little Mermaid appear in a local Blockbuster before the video releases of the Disney films. These films would have much lower animation and voice acting quality than the Disney films they were supposedly emulating, and some began to refer to the films by the colloquial term mockbuster.

Many mockbusters of both animated and live-action theatrical films are now made for the DVD market. The Brazilian company Video Brinquedo has made mockbusters of many popular Disney films, releasing titles such as The Little Cars and Ratatoing to Redbox kiosks and Amazon before the video releases of Cars and Ratatouille. Mockbusters of live-action blockbusters are even more common, and the film company The Asylum is one of the most prolific producers of them, “creating” such blatant ripoffs as King of the Lost World, Almighty Thor, and Paranormal Entity. However, their lucky streak of getting away with making blatant rip-offs of blockbusters may have finally run out; a lawsuit from Universal forced them to change the title and cover art of their Battleship mockbuster to American Warships. Despite this and the slow end of the DVD market, Asylum was able to transition into the second half of the 2010s better than most analysts could have possibly imagined - creating dozens more derivative movies, creating its own channel on PlutoTV to air them continually, and even coming up with an “original” franchise in the form of the six Sharknado movies. The Asylum’s success at maintaining its profitability and output means that there will be a near endless stream of low quality, poorly acted, derivative films with bad CGI being produced for anyone willing to watch them.

The video game industry has always seen some derivative products released. Early video game clones include The Great Giana Sisters, a Mario Bros. clone for early PCs that was removed from the market because Nintendo threatened to sue the game’s producers, and Fighter’s History, a blatant Street Fighter 2 clone that caused a lawsuit over copyright infringement upon its publication. Cloned games were also extremely common in nations such as Russia and China, including Somari, a Russian-made port of the Sonic the Hedgehog game to the NES that replaced Sonic’s sprite with Mario’s.

Truly blatant cloned games have become far more common with the advent of Apple’s App Store and Google Play. Unfortunately, some of these games not only infringe on copyrights but also install malware on the user’s device as well! Android’s strength as a platform is its open, PC-like nature, but this can become a weakness when a user downloads the wrong app, especially from storefronts other than the official Google Play storefront; earlier this year some cloned games and apps infected users’ Android devices at horrific speed. Android users should always use legit storefronts and be very suspicious whenever a “free” version of an obvious pay game or app appears in a digital storefront.

Even games that aren’t malware can easily be derivative, poor-quality clones. Some types of games are particularly conducive to being cloned; the incredibly simple Flappy Bird game now has over 800 clones available on various app stores, with more being released even to this day. Cloning is also rewarded in the mobile game industry as it has become increasingly focused on connectivity and marketing over quality; mobile companies continue to be acquired by major publishers for the value of their platforms and promotions rather than the derivative games they produce. The ease of mobile game development has been a powerful incentive for large corporations to clone and monetize the work of indie developers, as more Wall Street money pours into the bank accounts of major mobile publishers. With little means of protecting abstract ideas and game concepts (as opposed to actual code and assets), this type of legal cloning will likely continue in the foreseeable future, as Apple and Google have little capability to remove derivative works that don’t actually violate the law.

And let us not forget music. The most prevalent example concerning derivative works in music has been related to sampling. Sampling is the use of snippets of prerecorded, often popular, music as a backing track in a different song. A staple of 1980’s hip-hop, this process used to involve the actual cutting and splicing of tape.

One could conceivably take the best drumbeat from a James Brown record, the best background vocal from a Supremes song, and the best bassline from a Curtis Mayfield track. Put your own vocals over it, and you’ve got your very own supergroup...as long as you have the artist’s permission, that is.

Three of the densest examples of sampling are It Takes A Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back, by Public Enemy; Paul's Boutique, by The Beastie Boys; and 3 Feet High and Rising, by De La Soul. Note that all three of those albums were made within two years of each other. It was right when the technology was accessible enough, but the original copyright owners had not fully caught on to the fact that their music was being used without their permission. De La Soul specifically learned this the hard way when they were sued by the band The Turtles for using an uncredited sample. That lawsuit and several others established a precedent for sampling, permission rights, and royalties. Things do have a tendency to come full circle, though.

The digital technology of the past 15 years has transformed sampling from a long, arduous process to a simple task that even the most amateur songsmith can accomplish fairly quickly. The legal system and record companies have struggled to keep up with the ease and technology behind sampling. And so we’ve entered an age of mixtape culture and mash-ups. Once again I’d like to recommend three albums that best represent this new sampling culture:

The Grey Album by DJ Danger Mouse — Every drumbeat, every guitar lick, every bassline is from the Beatles’ expansive White Album. Meanwhile, Jay-Z lays down some of his best rhymes from The Black Album. Because copyright owners EMI did not authorize the use of The Beatles’ music, Danger Mouse chose to release his album for free download online. On “Grey Tuesday,” its release date of February 24, 2004, the album had over 100,000 downloads. Though the record companies did not approve, both Jay-Z and Paul McCartney have been quoted praising the record.

Night Ripper by Girl Talk — Greg Gillis was a biomedical engineer who just happened to also like DJing under a stage name on the side. Gillis gained attention through his upbeat juxtapositions of indie rock, pop, and hip-hop. When Notorious B.I.G.’s “Juicy” rubs elbows with Elton John’s “Tiny Dancer” magical things start to happen. With more than 150 sample sources, Night Ripper is Gillis’ first record made entirely of other artists samples, but he has upped the ante in recent years. His next albums, Feed the Animals and All Day, have over 300 samples.

Donuts by J Dilla — The previous two albums I have highlighted are fine in their own rights, but they also are a tad gimmicky. Focusing a whole album on two artists or trying to cram as many people into the dance party can be a distraction from making quality music. J Dilla was a respected hip hop producer who worked with De La Soul after their copyright lawsuit. As his career was advancing, so was a rare blood disease known as TTP. J Dilla was forced to stay in a hospital in the summer of 2005, and his friends brought him a sampling machine and a small record player to keep his mind and his spirit well-conditioned. During that time, Dilla was able to construct a beautiful, haunting record of less obvious samples. Also working in Donuts' favor is the fact that it is mainly an instrumental album. This both gives it a timeless quality and gives rappers a chance to use his tracks for their own albums.

Finally, we should talk a little bit about parody, especially because there is an actual Supreme Court case that specifically dealt with parody in pop music. It involves two artists who would normally never be mentioned in the same sentence: early rock icon Roy Orbison and shock rappers 2 Live Crew. Orbison’s “Oh, Pretty Woman” was a catchy, sweet pop song of its time. Three decades later, one of the most offensive rap groups of the early nineties wanted to create a parody song based on Orbison’s track. Their request to the record company was denied, but the group went ahead and made the song anyway.

When the case made its way to the Supreme Court, Orbison’s lyrics were compared to 2 Live Crew’s ode to a big hairy woman and her bald-headed friend. The vast difference between the songs’ subjects was enough of a defense for 2 Live Crew.

"Weird Al" Yankovic has never had to deal with a lawsuit or a Supreme Court ruling in his favor. That is because he always attempts to get the artists' permission to write parody songs of their latest hits. If they say no, he usually just moves on to another project. There have been a few times where a misunderstanding has led to a parody being made against an artist's will (Coolio’s "Gangsta’s Paradise" turning into “Amish Paradise” for example), but these have never led to the courtroom. Yankovic’s choice of playing by the rules and his prolific output over the past 30 years means that when "Weird Al" wants to parody your song, you should probably take it as a badge of pride.

All this and we’ve only faintly scratched the surface of derivative works. Keep your eyes and ears open, and you can probably catch a lot of your favorite books, music, movies, TV, games and more influencing each other. A good look at media’s past can reveal a lot about its present and future.