XII. That each Indian King, and Queen have equall power to govern their owne people and none to have greater power then other, except the Queen of Pomunky to whom severall scattered Indians doe now againe owne their antient Subjection, and are agreed to come in and plant themselves under power and government, whoe with her are alsoe hereby included into this present League and treatie of peace, & are to keep, and observe the same towards the said Queen in all things as her Subjects, as well as towards the English.

— Articles of Peace 1677

After the English

At the time the English first landed, there were an estimated 8,000 members of the Powhatan Confederation, consisting of about 30 tribes. By the 1660s, the number was estimated to be about 5,600--with only about 725 of those being warriors. Charles Campbell, in his History of the Colony and Ancient Dominion of Virginia, attributed the drastic loss in population to "disease, exposure, famine, and war; the rest were driven back into the wilderness."

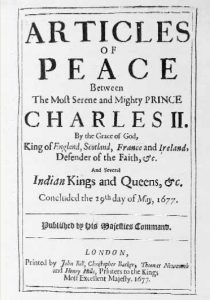

In 1677, 70 years after Jamestown's founding, the leaders of many of Virginia's tribes came together to sign the Treaty of Middle Plantation with the English settlers. Besides guaranteeing certain land rights and human rights to the tribes, the document (revised in 1680) also granted considerable power to the highly-regarded Queen Cockacoeske of the Pamunkey tribe. A relation to Matoaka (Pocahontas), Cockacoeske came to power after her husband Totopotomoi's (also written as Totopotomoy) death in 1656. He was a reliable ally to the British and was killed fighting against other tribes at the Battle of Bloody Run near Richmond.

A Woman Comes to Power

Totopotomoi's wife Cockacoeske assumed the role of Great Weroance (the English called her queen) but she had sway over a greatly reduced population, and most of the tribes who had accepted the rule of her father, the fierce English foe Opechancanough, were disinclined to follow his daughter.

Even so, the English believed Cockacoeske's claims to have dominion over several other tribes, and the 1677 Treaty of Middle Plantation and formalized in 1680 was written accordingly. The Queen had powerful allies in the House of Burgesses, including her paramour, Colonel John West. Colonel West, the son of provisional governor also named John West, was the first European child born along the York River. The town of West Point below Richmond is named for his family.

Two Sons Named John

Their union was not without controversy and scandal. John West had married Ursula (Unity) Croshaw, the granddaughter of Jamestown founder Raleigh Croshaw, in 1654. The couple had five children but their marriage to all intents and purposes ended when John West committed adultery with the Pamunkey queen. He went to live with Cockacoeske and is believed to have fathered several children with her, including a son who was also named John West. As the colonel and Unity also had a son named John West, this might have been a point of confusion. By 1691, such interracial relationships were forbidden by law and punishable by banishment, never mind that the marriage of John Rolfe and Cockacoeske's cousin, Pocahontas, had led to a period of peace between the settlers and the tribes decades before.

In 1676, Queen Cockacoeske appeared before a committee of the Governor's Council at Jamestown with her son, John West, and her interpreter in tow. The governor wanted her assistance in dealing with Nathaniel Bacon, whose rebellion eventually led to the torching of the state house. We are fortunate that an eyewitness to her appearance set down what is probably one of the most detailed descriptions of an American Indian noblewoman of Virginia ever recorded.

Hunted by a Rebel

The queen and her people suffered as a result of the rebellion. When Bacon and his followers set out to punish the Indians they struck at the peaceful tribes who had made treaties with Governor Berkeley, including the Pamunkey. Queen Cockacoeske and her followers were chased into Dragon Swamp. Men, women, and children were captured or killed. In the confusion, the queen became separated from the tribe and wandered, lost and starving, for quite some time.

An Uneasy Reign

The Chickahominy and the Rappahannock were among the tribes who did not take kindly to the submission to the Pamunkey queen, as required by the 1677 treaty. They argued that not since the days of her father Opechancanough had they been united under a Pamunkey ruler. But Queen Cockacoeske persevered, complaining to the British authorities that these subject tribes were not obeying her commands! Finally, the insurrection was put down, Bacon dead, and the traitors hanged--and one of those who sat judgment on them was the queen's own John West, himself having been captured by Bacon and his crew for some months. On June 5, 1678, Queen Cockacoeske came before the Council to ask for reparations for her losses. After some deliberation, they were granted, though by the Commission and not by the Council.

Queen Cockacoeske is believed to have died about 1686, according to a report made that year by the Pamunkey's interpreter, George Smith. As the Pamunkeys were a matrilineal people, her place might have been taken by one of her sons, but once more a queen was chosen to rule. Queen Ann, also known as "Ms. Betty Queen ye Queen," was Queen Cockacoeske's niece. Like her aunt before her, Queen Ann worked within the English laws and tried to unite her people.

Difficult Times

As the 1680s and 1690s wore on, the population of the Tidewater tribes decreased as did their land holdings. Some acres were sold voluntarily, but some were not. The Pamunkey and other tribes used the court system to try to hold on to their lands. They petitioned the governor, appeared before council and in so doing invoked the terms of the 1677 peace treaty. Relations with the colonists weren't their only worries. Aggressive incomers such as the Tuscarora, the Seneca and other tribes that lived above the fall line of the rivers attacked both the frontier settlers and the American Indians who served as their guides. In later years, the Virginia tribesmen would serve alongside the U.S. Army in the Civil War and numerous other engagements.

The Pamunkey, as well as other Virginia tribes, are with us today. The Pamunkey Reservation and museum draw visitors throughout the seasons. Some members of the Virginia tribes choose to live on the reservation while others may live in nearby. They keep many of their ancient customs and gather together at pow-wows to share their culture with each and the wider world. The historic events of the 1600s have not been entirely forgotten by either the tribes or the Virginia government. To this day, representatives of the Virginia tribes come to the state capital to present annual tribute—usually a deer—in acknowledgment that the treaties of 1646, 1677, and 1680 are still enforced.

The Pamunkey tribe preserves its independence to this day. According to its website, it has maintained its own governing body, which consists of a chief and seven council members elected every four years. The chief and council perform all tribal governmental functions as set forth by their laws. All of these laws are administered by the tribe itself.

A Different Century, Another Strong Woman Leader

Another strong woman of American Indian heritage is leading the Virginia tribes into the 21st century. G. Anne Nelson Richardson, whose childhood Indian name was Princess Little Fawn, became the chief of the Rappahannock Tribe in 1998. Her work to establish the predecessors of the eight modern Virginia tribes helped the Rappahannock win official state recognition in 1983. She has served the chair of the Native American Employment and Training Council and jas also served as executive director of Mattaponi-Pamunkey-Monacan, Inc., a consortium providing training and employment services for Virginia Indians.

When asked in 2000 the single thing she wanted the public to know about the Rappahannock, Richardson replied, "That my people still exist and will continue to exist. I think most people, when they think about the history of Virginia and the Indians in particular,… think about these things like the dinosaurs that existed and died and now we're writing about them and learning about them. But that's not the case with the tribes. They have vibrant communities that have been preserved for thousands of years."

Federal Recognition at Last

After many decades of work, in 2016, the 200-person Pamunkey tribe succeeded in getting federal recognition. Then in January 2018, President Trump signed into law a bill granting federal recognition to six other American Indian tribes in Virginia: the Chickahominy, the Eastern Chickahominy, the Upper Mattaponi, the Rappahannock, the Monacan ,and the Nansemond tribes. This recognition allows the tribal members, among other things, to access federal dollars that are available for housing, education, and medical care.

Remembering the Pamunkey Queen Today

One piece of the Pamunkeys' past is seen by thousands of history tourists every year. An engraved silver plate or frontlet was presented to Queen Cockacoeske by representatives of King Charles II. It has survived through the centuries and may be seen on display at NPS Jamestown, although it was repatriated to the Pamunkey Tribe in 2017.

In the future, visitors to Richmond, Va., will be able to see a statue of Queen Cockacoeske in the "Voices from the Garden" monument, part of the Virginia Women's Monument in Memorial Plaza.

Sources for the article:

[1705] The Beginning, Progress, and Conclusion of Bacon's Rebellion in Virginia in the Years 1675 & 1676. In Tracts and Other Papers, vol. 1 (8), ed. Peter Force. New York: Peter Smith. 1835.

"Cockacoeske, Queen of the Pamunkey, Diplomat and Suzeraine," by Martha W. McCartney, in Powhatan's Mantle: Indians in the Colonial Southeast, by Gregory A. Waselkov, et al., pp. 243-266

"Persons Who Suffered by Bacon's Rebellion." The Commissioners' Report The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 5, No. 1 (Jul., 1897), pp. 64-70

Available through JSTOR

A Study of Virginia Indians and Jamestown: The First Century, edited by Danielle Moretti-Langholtz. December 2005

"West, Colonel John" in Encyclopedia of Virginia Biography, edited by Lyon Gardiner Tyler, page 356.

For Related Information:

"'Delaware Town' and 'West Point' in King William County, Va." by Malcolm H. Harris, The William and Mary Quarterly, Second Series, Vol. 14, No. 4 (Oct. 1934), pp. 342-351

More on the West family's settlement near the Pamunkey. Available through JSTOR.

Elsing Green

One of the West family homes, dating to the late 1600s, may be visited today by appointment.

Executive Journals of the Virginia Colonial Council

The compiler was commissioned to digitize all references to Indians indexed in the "Executive Journals of the Virginia Colonial Council." The journals were kept from 1680 on, but few mentions of tribes are made after the 1740s.

History of the Colony and Ancient Dominion of Virginia by Charles Campbell, copyright 1860.

This very old online book has more details of settlement, early government, and warfare in Virginia history up through the time of the American Revolution than most modern texts. Includes an index.

The New World starring Colin Farrell, Christopher Plummer, and Christian Bale

The directors of this beautiful retelling of the John Smith-Pocahontas legend consulted with and cast local tribal descendants for the making of the film.

Pocahontas's People: The Powhatan Indians of Virginia through Four Centuries by Helen Rountree

Anthropologist Helen Rountree examines the history of the tribes who once followed Powhatan to the modern era.

Virginia's First People: Past and Present: History

Prince William County Schools' online initiative gives lesson plans and other instructional resources on "Virginia's First People."