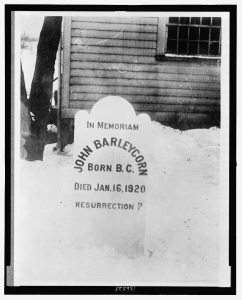

January 17, 1920, saw a massive sea change in American law as the 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution went into effect. Prohibition became the law of the land, and a once vibrant consumer alcohol industry and way of life in the United States was abruptly replaced with a top-down directive that imposed unprecedented federal control over the lives of American citizens. The age of Prohibition would last slightly longer than a decade, and in its relatively short duration, would have a massive impact on the American culture of alcohol consumption, organized crime, and even cuisine. Prohibition’s effects on the American psyche and shared memory can still be felt today, long after the battle over the national law ended.

Before the Dry Days

The United States in its early existence was a nation with very localized legal codes and law enforcement. Prior to the Civil War, the main legislative battleground for moralists was slavery and which states (if any) should be admitted as slave states. As enmity grew between pro- and anti-slavery legislators, and Northern abolitionists became increasingly driven to end slavery nationwide, very little national legislative effort was devoted to other social reforms. Early anti-alcohol legislation, such as the 1851 “Maine Law”, was applied only on the basis of state-specific law. Even the Maine Law, which initially prohibited both the manufacture and sale of alcoholic beverages, was replaced in 1858 with a different law that allowed the limited sale of alcohol as a beverage. Only after 1865 and the abolition of slavery in the aftermath of the Civil War would a true national push to ban alcohol emerge in the American psyche.

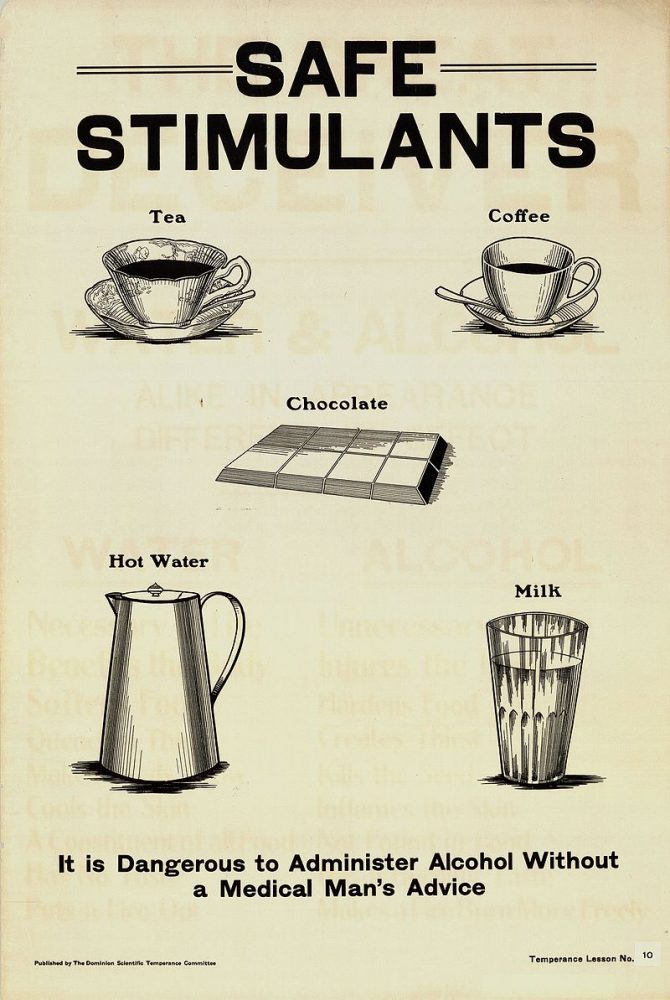

As America’s westward expansion brought with it new territories and citizens trying to stake out a piece of their Manifest Destiny, a macho “saloon culture” flourished. Small towns and large cities alike had saloons, local businesses that employed bartenders who could make mix drinks. The popularity of saloons was no accident, and was in fact linked to the increasing popularity of beer among the American populace. Many saloons were in fact “tied houses," being supported and financed by specific brewers for the purpose of selling that company’s beer. Free food was often offered to men who drank enough as an incentive for customers to buy as much alcohol as possible!

The Road to Forced Sobriety

As saloons flourished, beer’s popularity increased, eventually becoming one of the major manufacturing industries in the United States. German immigrants furthered beer’s popularity by changing the typical American beer from British-style ale to German lager beer, which was extremely popular among German-Americans and other immigrants from continental Europe. Large breweries such as Pabst and Anheuser-Busch had emerged by the end of the 19th century and were beginning to gain market share with a new innovation that allowed them to get their product to more saloons - bottled beer. Even as large breweries continued to expand their market share and new saloons opened, the alcohol industry’s expansion had made it increasingly dangerous and powerful enemies.

The road to Prohibition was an intersection of America’s political right and left, who both found prohibitionist legislation attractive for different sets of reasons. On the right, America’s Protestant establishment saw the rising saloon culture and appetite for beer as manifestations of cultural change wrought by Catholic immigrants. The drive for a “Protestant Identity” movement to rival the influence of Catholics led to the formation of the Anti-Saloon League, a powerful organization with the support of powerful mainline Protestant denominations of the time, especially the Methodists and Baptists. Republicans were particularly supportive because of the common stereotype that only Democrats (i.e. Catholics) were saloon owners. Even far-right groups found empowerment in the prohibitionist cause as the Ku Klux Klan, which had largely disbanded after the end of Reconstruction, found a second wind as Hiram M. Evans sought to use the anti-alcohol cause as a means to expand the KKK beyond its traditional Southern borders. Wayne Wheeler, the head of the Anti-Saloon League, sought allies against the alcohol industry for any reason, and accepted a tacit alliance with the KKK against Catholics and Jews, who were both associated with the alcohol industry.

The Anti-Saloon League also accepted more progressive groups as potential allies in its war on America’s saloons. The Women’s Christian Temperance Union was an early political voice for women in America and was devoted to ending America’s consumption of alcohol. The WCTU became associated with progressive politics during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, becoming involved with movements for labor laws, prison reform, and women’s suffrage. American politics became increasingly nationalized in the Progressive Era, and alcohol was blamed for numerous societal problems, including public health, childhood diseases, and the effects of rapid industrialization on the once-rural American culture. With support across the political spectrum, prohibitionists rapidly advanced the Volstead Act through the House and Senate, even gaining enough support to override President Woodrow Wilson’s veto on October 28, 1919. On January 17, 1920, Prohibition came into force, and a new era in American law began.

A Bitter Age: Prohibition’s Negative Effects on America

Prohibition’s negative effects on American society were rapid and far-reaching, and it caused the end of many small businesses, created powerful organized crime syndicates, and assisted in creating a xenophobic and racist national atmosphere in the 1920s. The first recorded defiance of Prohibition occurred within an hour of it coming into force, setting the stage for an era of bootleggers, gangsterism, and illegal alcohol consumption. The Sicilian Mafia, once an organization largely limited to street crime and protection rackets for Italian immigrants, became an incredibly powerful crime syndicate with many powerful leaders. Men like “Lucky” Luciano, “Bugsy” Siegel and Frank Costello became obscenely wealthy and powerful in the New York Mafia scene, and the dreaded Five Families of New York would arise to dominate the world of bootlegging and other criminal enterprises through their profits. The massive financial windfall of Prohibition would create a powerful crime boss in Chicago as well--the infamous Al Capone. Capone took advantage of the incredible revenues of bootlegging to bribe numerous policemen and established an alliance with the mythically corrupt mayor of Chicago, “Big Bill” Thompson so that they could both maintain a firm grip on power over the city. Though Capone’s time in power was not long, ending in 1929, the Chicago Outfit he built with the profits from Prohibition was massive and powerful for decades afterward. The mere fact of Prohibition’s existence had created powerful criminal institutions that would not only prosper for its duration, but exist forever afterwards to plague Americans with extortion, murder and corruption.

Prohibition would also distort the American alcohol industry by killing off numerous smaller breweries and wineries, allowing large businesses to survive via clever gimmicks and legal workarounds rather than brand quality. Large national breweries, such as Pabst, Schlitz, and Anheuser-Busch, had already acquired larger market shares than most local brewers, and even though their revenues were impacted by the imposition of Prohibition, they quickly developed schemes to stay in operation and increase their market power even further. One popular method of doing so was the creation of “near beer,” a product that fell under one half of one percent of alcohol. Another popular solution was to produce malt syrup, supposedly an ingredient for making cookies but mainly used by home brewers to make their own alcohol. Some very specific businesses introduced by large breweries trying to adapt included Yuengling’s conversion to an ice cream manufacturer, Coors’ ceramics business, and Pabst’s cheesery.

Some large wineries survived Prohibition as well by developing a new way to get their wine grapes out to the customers called wine bricks. Rather than tear up their vineyards and sell their land, some winemakers determined that they could sell their wine grapes directly to consumers compressed into solid bricks so that the buyers could make their own wine from them. Prohibition forbade the sale of grapes for alcoholic consumption, but allowed it if warnings were listed on the packaging that the grapes not be used to make wine. Companies could exploit this by providing “warnings” that were in fact exact instructions as to how to make the wine brick into wine, as long as they were phrased as what not to do with the brick. The vineyards that took this route to profitability, such as the Beringer vineyards, gained a tremendous share in the American “wine” market. Although many brewers and vineyards closed during the restrictive Prohibition era, the survivors gained an overwhelming market share, turning the American alcohol industry into an oligarchy that would endure until the craft brewing era of the 1980s.

Strange Victory: The Unusual Upside of Prohibition

As potent as the downsides to the Volstead Act were, it did have one major benefit that often goes unnoticed in historical analysis because it pertained to biodiversity rather than business or organized crime. Turtle soup was once a beloved menu item for Americans, and had been widely consumed since the middle of the 19th century. Diamondback terrapins were the type of turtle most used to make the soup, which also required sherry or Madeira wine for flavoring and to ensure the cleanliness of the turtle. The slow-breeding diamondbacks were decimated as they were harvested at a voracious pace, greatly reducing the wild turtle population and raising the price of turtle soup to the point that non-wealthy people had to resort to dishes like Heinz’s pre-prepared turtle soup in order to get their favorite food. Prohibition made it impossible to obtain sherry easily, and turtle soup disappeared from the menu of many of the luxury restaurants that had made it a specialty. It would take decades for the populations of diamondbacks harvested before the onset of Prohibition to slowly reestablish themselves and reach the genetic diversity they once had before turtle soup was popular. If Prohibition had never occurred, diamondback terrapins very well could have joined the passenger pigeon on the list of American animals eaten into oblivion.

Closing the Chapter: End of a Failed Amendment

Prohibition was finally repealed on December 5, 1933 with the passage of the 21st Amendment, and was considered a rare business victory for a nation that had become mired in the Great Depression. With businesses collapsing and tax revenues plummeting, the nation could no longer afford to ban potentially lucrative industries, and Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s massive electoral victory gave him a mandate to pursue whatever policies he wished. Though Prohibition was short-lived compared to most constitutional amendments, the scars it inflicted on America were long-lasting and deep. Restaurants, breweries, and wineries closed, damaging the American culinary landscape. Criminals gained power once unheard of in American society, leading to the creation of the term “organized crime” to describe the grim new reality. Surviving breweries and wineries gained massive amounts of market share, diminishing local flavor and leading to an era of mass-produced beer and wine. Although the cause of creating a cleaner, less violent America was admirable, Prohibition did not achieve the desired result, and lingers on in the American memory as a failure of social engineering to change society’s desires.

Discover the long-winded and crazy story of the thirteen years where alcohol was bad news for the nation through these books.