Known for his witty prose, plots revolving around comedic errors, and the characters of Jeeves & Wooster, P.G. Wodehouse was one of the great British comedic writers of the 20th century. His writings won him many readers in the first half of the 20th century and became the basis of a popular PBS series in the early 1990s. Wodehouse’s gifts for characterization and description in writing make his short stories a delight to read in any decade. Wodehouse’s unusual life, split between the United Kingdom and New York, was a major influence on his work, providing him with an understanding of the differences between the British and American upper classes and exposing him to a unique social scene that would inspire his characters’ many ridiculous adventures.

School Days: The Beginning of Wodehouse’s Writings

Pelham Grenville Wodehouse was born in the UK in the county of Surrey to Henry Ernest Wodehouse, a British judge who worked in the colony of Hong Kong. Although he spent his earliest years with his parents in Hong Kong, he was sent back to England at the age of two and grew to his teenage years hardly knowing or seeing his parents. Most of his time during these years was spent at a series of boarding schools, and his main contact with the rest of his family consisted of staying with a variety of aunts and uncles on school holidays. Aunt Agatha, Bertie Wooster’s powerful and controlling aunt, was strongly influenced by Wodehouse’s early exposure to his own intimidating aunts during these times. Wodehouse enjoyed his teenage years at Dulwich College, where he distinguished himself in sports, singing in school concerts, and editing the school magazine. Wodehouse could not follow his brother Armine into the University of Oxford because the family’s income fell at a critical juncture, and he was forced to take a job at the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank’s London branch in order to provide for himself financially. It was during his time in this job that his real talent as a writer would bear fruit.

Early in his writing career, Wodehouse worked mainly in the genre of school stories. His earliest novel, The Pothunters, was published in 1902, beginning a period of experimentation with genre and style before he settled on the PG Wodehouse template. It would take until 1908 for him to create his first truly memorable character in his final school story, Mike, which introduced Psmith, the first member of Wodehouse’s fictional gentlemen’s association, the Drones Club. A thin young man with a monocle, a generous soul, and a gift for wordplay, Psmith offered Wodehouse the first opportunity to explore his gift for writing comedic dialogue. Unlike the later Bertie Wooster, the quintessential “gentleman without a job,” PSmith worked in a variety of occupations, including banking (Psmith in the City), journalism (Psmith, Journalist), and visiting Blandings Castle in search of work (Leave It to Psmith). Psmith was Wodehouse’s first critically acclaimed character and would eventually be followed by an even more memorable member of the Drones Club, Bertie Wooster.

The Birth of Bertie: Wodehouse Creates His Most Popular Character

Bertie Wooster originated as “Reggie Pepper,” first appearing in the short story “Absent Treatment” in 1911. Reggie possessed most of the qualities that would define Bertie even at this early date: a carefree attitude, infinite financial reserves freeing him from a need for employment, and an amazing ability to bumble into massive amounts of trouble with each scheme he enacts. Reggie stories tended to be formulaic comedies in which Reggie tries to help one of his friends - typically involving a problem with a wife or girlfriend - and enacts some scheme to help his friend that makes the problem worse and causes much chaos and confusion. The value of the stories wasn’t in the programmatic plots but in Reggie’s witty first-person narration, Wodehouse’s unique gift for dialogue, and the many strange upper-class characters wandering through the stories’ gilded world. As entertaining as Reggie’s narration and characterization was, he lacked a character he could play off of that would truly accentuate his unworldliness and poor sense of judgment. Wodehouse would revise the character, giving his first name “Reggie” to a new valet character, Reginald Jeeves, and renaming Pepper “Bertie Wooster.” Jeeves was the exact opposite of Bertie: unflappably calm with indisputably good judgment and a vast amount of knowledge regardless of the situation. It would fall on Jeeves to somehow salvage every preposterous situation that Bertie had created and make things better than they were before...or somehow concoct a lie that barely saved Wooster yet again. Jeeves and Wooster became Wodehouse’s most popular characters following the publication of My Man Jeeves in 1919.

Over the 1920s and 1930s, Wodehouse would publish numerous books chronicling the misadventures of Wooster and Jeeves. The Inimitable Jeeves was published in 1923, followed by Carry On, Jeeves in 1925 and Very Good, Jeeves! in 1930. These early books were collections of short stories, often originally published in various magazines, with some Reggie Pepper stories rewritten into Jeeves stories to provide more material. Wodehouse would continue to develop the characters of Jeeves and Wooster as he switched from the short story format into novel-length narratives, making Wooster a member of the Drones Club like Psmith and developing even more elaborate schemes for him to bungle. The first full-length Jeeves and Wooster novel, 1934’s Thank You, Jeeves, saw Jeeves leaving his master’s employment after the auditory torture of Wooster’s banjolele playing became too much even for him, forcing Bertie to resolve a plot involving his former fiance with an unusual lack of help from Jeeves. Jeeves and Wooster were reconciled at the novel’s end, and their relationship began to change over later novels such as 1938’s The Code of the Woosters; Wooster slowly became more dependent and less likely to rebel against Jeeves, who became ever more indefatigable and useful in Wooster’s life.

Empire’s End: World War II and Wodehouse’s Departure From Britain

Although the 1920s and 1930s were very kind to P.G. Wodehouse, his own lack of worldliness and globe-trotting lifestyle would finally catch up with him in the 1940s and the advent of World War II. Wodehouse and his wife were staying at their house in France even as World War II had begun, as he working on the Jeeves novel Joy in the Morning. Wodehouse himself was offered a spare seat in one of the fighter aircraft as the Royal Air Force base withdrew from the German advance, but he refused it, as it would mean leaving behind his wife and dog. The Germans captured Le Touquet, on May 22, 1940, and Wodehouse was interned two months later. He was sent to Tost in Upper Silesia, where he attempted to continue his writing and retained his characteristic lighthearted nature and good humor.

Sadly, what had once bound him to the popular zeitgeist and made him popular among his nation’s people would now become a source of division from them. His isolation from his nation (his capture came before the evacuation of Dunkirk, one of the defining events of the war for the British) and extreme naivete about politics caused him to put out an ill-conceived interview with the New York Times titled “My War With Germany” where he made light of his captors. The Germans exploited this, commissioning him to do five comedic broadcasts about his internment largely for his American fan base. Wodehouse’s broadcasts were apolitical in nature and were comprised of humorous anecdotes about him and his captors rather than pro-Nazi or anti-British propaganda, but the reaction among the British public was furious, as they saw any broadcasting for the Germans as collaboration. After the Allies reclaimed Paris in 1944, Wodehouse was in French custody, where he would be extensively investigated as a Nazi collaborator by both French and British authorities. MI5 investigated Wodehouse as a potential British renegade in 1944, determining that the broadcasts were not pro-German in nature or designed to assist the enemy, but the damage had already been done to Wodehouse’s reputation. After the French finally dropped charges of Wodehouse in June 1946,he made arrangements to leave for America, where he would live the rest of his life.

P.G. Wodehouse was a brilliant literary talent but was also strongly bound to being a voice of a specific place and time. His short stories retained their early 20th-century settings and late British Empire gentlemen into the 1970s, long after the end of World War II and the sunset of the British Empire. Though he lived over 90 years, his characters and settings retained the style he established in the 1910s, preserving a certain type of wit and literary craft long after the scene that originally inspired it had vanished into history. The resentment between Wodehouse and the British government spawned from World War II would never truly heal; he only received knighthood shortly before his death in 1975 and was too old and sickly to personally travel to Britain to receive the honor. It seemed oddly fitting for a writer who had exiled himself from the nation of his birth for decades and become an American citizen long ago to be so disconnected at the time of his final triumph. Wodehouse’s literary world, a lost paradise of gentlemen with no jobs but unlimited money and a bottomless appetite for bizarre schemes, hovered in the back of both the American and British psyches and outlasted the British government’s enmity of him. It would live on in the popular imagination to inspire one of the great Britcom TV series.

Legacy of Laughter: Adapting Wodehouse for Television

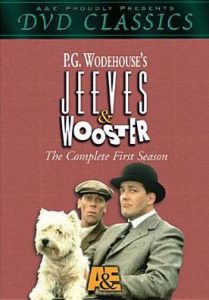

In 1990, ITV and PBS debuted the TV series Jeeves and Wooster. It starred Hugh Laurie as Wooster and Stephen Fry as Jeeves, and they were likely cast together in the lead roles because of their considerable prior history as a double-act on British TV. Initially Laurie and Fry were reluctant to take on the roles of the beloved characters, but decided to, knowing the series would be made no matter what and felt they could do the greatest justice to Wodehouse’s characterizations. Laurie was a wonderfully air-headed and harebrained Bertie Wooster, his self-absorption matched by his shortsightedness, with an amazing talent for expressing joy at the “brilliance” of his ridiculous schemes. Fry was perhaps slightly younger than the Jeeves of the novels but was absolutely perfect in every other sense, with a wonderfully deep voice to convey his superior intellect and rationality, using only the subtlest of facial expressions and changes of tone in his voice to register disapproval with the most ludicrous of Wooster’s ideas. Once you’ve seen Fry and Laurie as Jeeves and Wooster, it will prove very difficult to disassociate them from the characters in your mind. The series made wonderful use of music throughout, especially its distinctive theme music and Laurie’s frequent renditions of popular songs of the 1920s and 1930s. Many of the plots were adapted directly from Wodehouse’s stories, often combining the events of two stories into one episode to form a longer narrative for the hour-length format of the series. Jeeves and Wooster ran for four seasons and 23 episodes, packing more laughs into its relatively short run than many American sitcoms at double or triple the length. It was a great tribute to Wodehouse’s work and a fitting effort to preserve his characters in a visual medium.

In 1990, ITV and PBS debuted the TV series Jeeves and Wooster. It starred Hugh Laurie as Wooster and Stephen Fry as Jeeves, and they were likely cast together in the lead roles because of their considerable prior history as a double-act on British TV. Initially Laurie and Fry were reluctant to take on the roles of the beloved characters, but decided to, knowing the series would be made no matter what and felt they could do the greatest justice to Wodehouse’s characterizations. Laurie was a wonderfully air-headed and harebrained Bertie Wooster, his self-absorption matched by his shortsightedness, with an amazing talent for expressing joy at the “brilliance” of his ridiculous schemes. Fry was perhaps slightly younger than the Jeeves of the novels but was absolutely perfect in every other sense, with a wonderfully deep voice to convey his superior intellect and rationality, using only the subtlest of facial expressions and changes of tone in his voice to register disapproval with the most ludicrous of Wooster’s ideas. Once you’ve seen Fry and Laurie as Jeeves and Wooster, it will prove very difficult to disassociate them from the characters in your mind. The series made wonderful use of music throughout, especially its distinctive theme music and Laurie’s frequent renditions of popular songs of the 1920s and 1930s. Many of the plots were adapted directly from Wodehouse’s stories, often combining the events of two stories into one episode to form a longer narrative for the hour-length format of the series. Jeeves and Wooster ran for four seasons and 23 episodes, packing more laughs into its relatively short run than many American sitcoms at double or triple the length. It was a great tribute to Wodehouse’s work and a fitting effort to preserve his characters in a visual medium.