The most famed and prolific area of science fiction is the planetary adventure, featuring strange environments, exotic alien races, and massive battle scenes. Many of the most popular science fiction universes, such as Star Wars, Star Trek, and Avatar, take place in these environments. Most of these universes owe their existence to the adventure fiction of one author.

The most famed and prolific area of science fiction is the planetary adventure, featuring strange environments, exotic alien races, and massive battle scenes. Many of the most popular science fiction universes, such as Star Wars, Star Trek, and Avatar, take place in these environments. Most of these universes owe their existence to the adventure fiction of one author.

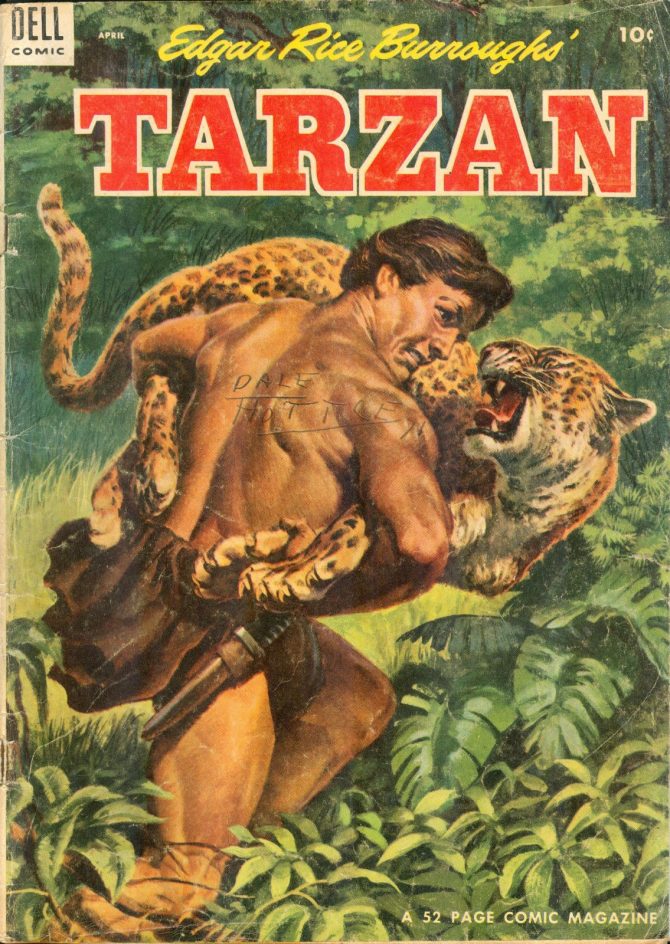

Edgar Rice Burroughs wrote popular adventure fiction throughout the first half of the 20th century. Although best remembered today as the author of the Tarzan books, Burroughs created many other characters and series as well. One of the most influential was set on the planet Barsoom, otherwise known as Mars. In some ways, Barsoom was already a familiar literary universe for Burroughs’ readers. The stories relied heavily on encounters with dangerous creatures and lost civilizations, and the main characters have many similarities to those of the Tarzan books. Though not a trained linguist, his gift for developing imaginary languages was also utilized in creating the Barsoom language.

Yet Barsoom is stunningly different from any other environment Burroughs created due to its ecology. Unlike the jungle environments Burroughs favored in almost all the other adventure stories he created, Barsoom was a desert of barren sea bottoms, arid plains, and savage four-armed green nomads. The environment of Barsoom is so forbidding that the reader feels wonder and awe when Earthling protagonist John Carter first arrives there.

The theoretically more civilized aspects of Barsoom are nearly as harsh and alien as its barbarism. Cities with amazing technologies are nonetheless constantly at war, ruled by a red-skinned humanoid race. The frequent scenes of Red Martians engaging each other in sky battles with massive airships make for a compelling read, and they seem to have strongly influenced George Lucas’ visual imagination for the massive starship battles in the Star Wars films.

Barsoom’s wildlife proved just as influential to the sci-fi adventure genre as its technology and setting. Because the Red Martians remain at a feudal level of social organization throughout the entire series despite their amazing capacities for medicine and engineering, large parts of the planet are either completely wild or under the control of lost civilizations isolated from the rest of Barsoom. A good portion of the wildlife consists of creatures that resemble the Earth animal whose ecological niche they fill, usually with a certain amount of change in appearance/size, such as the dog-like Calot, and the lion-like Banth.

However, other creatures such as the bizarre carnivorous Plant Men bear so little resemblance to any Earthly life form that they appear uniquely monstrous and frightening to the reader. The most interesting specimens in Barsoom’s menagerie appear in The Chessmen of Mars: the spider-like Kaldanes. Intelligent and capable of rational thought and speech, the Kaldanes have advanced much further in their mental evolution than their physical. Lacking hands, they must attach themselves to headless humanoid beings called Rykors in order to move about and perform most tasks. Burroughs used the Kaldanes and Rykors as a metaphor for the dangers of separating intellect and physical activity in human beings, literally making the mind and the body two separate entities.

Barsoom proved to be one of Burroughs’ most popular fiction settings. Ten Barsoom novels were published, and multiple comic strip adaptations were produced, some illustrated by Burroughs’ son John Coleman Burroughs. Although the series is considered one of the most influential in modern science fiction and has inspired many references in films and television series, an actual screen adaptation of the Barsoom series has not yet been produced.

The story behind this is one of the great tragedies of the animated film industry. In 1931, Bob Clampett, one of MGM’s top animation directors, successfully negotiated a deal with Burroughs to make an animated production of Burroughs first Barsoom novel, A Princess of Mars. In 1936, Clampett used rotoscoping (animation traced over live-action movement) to create test footage of short scenes from the novels. However, theatre owners panned the project, claiming that the concept was too bizarre to sell to adult audiences, and the film was canceled. Ironically, Clampett’s belief in the commercial viability of a science fiction series would be vindicated by another project released that year.

Enter Flash Gordon

In 1934, Alex Raymond began illustrating the newspaper comic strip Flash Gordon. The strip became popular due to its vibrant colors and exciting artwork, especially in its battle sequences. It became so popular that Universal began making serial films based on the property. The first, entitled Flash Gordon, premiered in April 1936, and became hugely popular with matinee audiences. Universal responded by creating two more serial films, Flash Gordon’s Trip to Mars (1938) and Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe (1940).

Although Raymond stopped illustrating the comic strip in 1943, other illustrators and writers kept creating new stories until 2003. Raymond’s work on the series is considered some of the best Sunday comic strips produced and has been reprinted by several publishers. The Universal serials are also highly regarded; the 1936 film has been selected for preservation in the Library of Congress.

Modern perceptions of the Flash Gordon film series tend to regard it unfavorably in comparison to many of the works that it influenced, including Star Wars and Star Trek. This is partly because many of the concepts that Flash Gordon utilized, such as faster-than-light space travel, exotic alien races, and megalomaniacal villains, have become so widely utilized in the science fiction genre that people no longer associated them with the series in which they were originated.

A notable example of this occurred when the 1980 feature film version of Flash Gordon was released. It was widely panned by film critics of the time as “ripping off Star Wars,” even though Star Wars extensively used ideas and concepts pioneered by Flash Gordon. Interestingly, the film gained a cult audience over time, due to its camp nature and entertaining theme music by Queen, as well as Brian Blessed’s enjoyably hammy performance as the hawkman Prince Vultan.

Another aspect often criticized by modern audiences is Flash Gordon’s principal villain, Ming the Merciless. He is often viewed as a Fu Manchu-style Asian stereotype due to his physical appearance and characterization. Writers of the series began making an effort to shift his characterization away from these stereotypes as early as Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe, in which he was portrayed more as a Hitleresque dictator, but the original characterization and appearance remain a topic of criticism by contemporary audiences.

Although these two series that initially popularized adventure science fiction may seem marginal or obscure to some of today’s audience, many of the novels and films featuring them remain surprisingly enjoyable. The ingenious world-building and imaginary languages of Burroughs remain vivid and compelling to even a jaded modern audience, and the Flash Gordon serials are perhaps the best sound serials produced by a Hollywood studio.