By Barbara Crookshanks

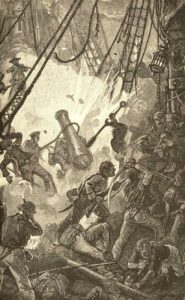

The time was sunset on Sept. 23, 1779. A full moon was rising. The place was the bloody deck of John Paul Jones’ ship the Bon Homme Richard. There a young Spotsylvanian named Laurence Brooke would show the stuff of which heroes are made. At age 21, he was the lone surgeon on the Bon Homme Richard as it engaged the 50-gun HMS Serapis in the North Sea off Scarborough, England. The burning Serapis surrendered after a 3 1/2-hour battle during which John Paul Jones proclaimed: “I have not yet begun to fight!”

It is said that the blood ran ankle-deep as Laurence Brooke tended to more than 100 wounded and dying. And an excellent job he did, according to Nathaniel Fanning, midshipman on the Bon Homme Richard:

“He was the only surgeon in the fleet who really knew his duty ...this man was as bloody as a butcher from the commencement of the battle until towards night of the day after. The greater part of the wounded had their legs or arms shot away, or the bones so badly fractured that they were obliged to suffer under the operation of amputation. Some of these poor fellows having once gone through this severe trial by the unskilled surgeons, were obliged to suffer another amputation in one, two, or three days thereafter by doctor Brooks; and they being put on board the different vessels composing the squadron, made it difficult for doctor Brooks to pay that attention to them which their cases required: besides, the gale of wind which succeeded the action, and which I have made mention of, made it altogether impracticable for him to visit the wounded, he being all this time on board the Serapis, excepting such of them as were on board of this ship. (From Fanning's Narrative)

From Student to Surgeon

The adventure had begun in 1774 when Richard Brooke, wealthy owner of Smithfield plantation four miles south of Fredericksburg on the Rappahannock River, sent his two oldest sons, Robert, 23, and Laurence, 16, to Scotland. There at Edinburgh, Laurence would study medicine and Robert law. When the American Revolution interrupted their studies, the young men escaped to France. Robert was captured by the British, escaped and was captured again, but finally managed to get home on a French ship. He joined the two younger Brooke brothers—twins Francis and John—in the Continental Army.

Laurence remained in France, and early in December of 1778 journeyed from Paris to Nantes, an inland port on the Loire River in western France, where the Bon Homme Richard was anchored. Armed with a letter of recommendation from Benjamin Franklin, the medical student offered his services to Jones. An admirer of Franklin, Jones had named the Bon Homme Richard for his Poor Richard’s Almanack. Franklin, John Adams and Arthur Lee were in France as American commissioners. Jones evidently trusted Franklin’s judgment. Also, the future “Father of the American Navy” was familiar with the prominent Brooke family. He had spent two years in Fredericksburg with his tailor brother, William Paul. So Brooke received his commission as ship’s surgeon.

On board the Bon Homme Richard he became a great favorite, especially with two future presidents of the United States. On Feb. 12, 1779, John Adams and his 12-year-old son, John Quincy Adams, visited the Bon Homme Richard, which had sailed farther up the French coast to dock at L’Orient.

In his diary, the elder Adams had nothing but praise for Brooke, who visited Adams’ ship the next day “and drank tea with me. He seems to be well acquainted with philosophical experiments and I led him to talk about this subject.

“He had much to say about phlogiston [a theory of combustion] …I led him to talk of the ascent of vapors in the atmosphere, and I found he had considered the subject.” Brooke also told Adams of a natural history of North and South Carolina “in four volumes, folio, with stamps of all the plants and animals.” In his diary Adams also noted that he, Jones and Brooke dined at L'Epee Royal in L’Orient.

The next day Adams was ill with a cold on his own ship and reported that “Dr. Brooke came and took tea with me.” Adams also noted that Brooke was a gentleman of family “whose father has a great fortune and character in Virginia.” This was true. Richard Brooke, described by his son Francis as “a handsome man with great vivacity of spirit,” built Smithfield in the mid-18th century. He named the family home—and his son Laurence—for Laurence Smith, commander of the fort built there in the 17th century to defend the region from Indians.

Laurence’s grandfather, Robert Brooke of Essex County, had come to Virginia about 1710 and became Surveyor of Virginia and was a member of Gov. Spotswood’s Knights of the Golden Horseshoe. Although Laurence Brooke impressed John Adams favorably, John Paul Jones did not: “Eccentricities and irregularities are to be expected from him. They are in his character; they are in his eyes.”

Goodbye to the Navy

Laurence Brooke had been highly commended for his performance during the Sept. 23 Bon Homme Richard—Serapis affair. However, by early December he was not a happy young man. On board Jones’ new ship, the Alliance, Brooke expressed an overwhelming desire to leave the Navy. He gave his “state of mind” as a reason. On the morning of Dec. 5, 1779, he could contain himself no longer. Although both were on board the Alliance, he sent Jones a letter saying: “I am determined never more to serve as a surgeon in the Navy unless compelled to serve by the utmost necessity. I am therefore induced to request that you will be so kind as to give orders to the Commanding Officer upon deck to suffer me to leave this ship with my baggage.”

Jones penned a testy and rather sarcastic reply saying that the Rules of Service would not be subverted to suit his private views. He reminded Brooke that just a few days earlier his health had appeared to be good. Brooke responded sharply: “Your letter…is diffusive in matter, but affords me no satisfaction…it rather appears to be studiously framed to evade my purpose.” Then he delivered a slightly-veiled threat: “I hope you will never by an undue use of any power which may be committed to you by the States of America give any of their Subjects cause of Complaint.”

The real background behind this exchange is shrouded by time. Brooke did not leave the ship immediately, but did not sail with Jones to Philadelphia in 1781. Historians surmise that he received his M.D. degree at the Paris Medicinal University and perhaps enjoyed typical youthful pursuits while there. Some years later, the American government paid him $141.41 for his service with John Paul Jones.

Return to Smithfield

Whatever may really have happened during the years in France, in August 1783, Brooke returned home after nine years abroad. He began the practice of medicine at Smithfield. Brooke would lead a much more private life than his three brothers, who would soon be in the public eye. Robert, builder of Fredericksburg’s Federal Hill, would become governor of Virginia, State Attorney General, and Grand Master of Virginia Masons. Francis would become Chief Justice of Virginia, serving on the Virginia Court of Appeals for 40 years. John would become the first president of the Farmers’ Bank (later the National Bank of Fredericksburg).

Richard Brooke died at age 60 in 1792, the same year John Paul Jones died. Brooke was the executor of his father’s estate. The settlement evidently resulted in the sale of Smithfield to Thomas Pratt. The land is now the site of the Fredericksburg Country Club. The same year his father died, the 34-year-old doctor moved to Fredericksburg and rented a house that Dr. Charles Mortimer had built at either 214 or 216 Caroline Street. Brooke and his wife, the former Frances Thornton, were the parents of two daughters. Gordon, perhaps relying on memories handed down from past generations, described Dr. Brooke as “clever, entertaining and very humorous.” It is also reasonable to expect that he retained the love of learning and intellectual curiosity that had made him such a favorite with John Adams.

Brooke’s second and last home in Fredericksburg was at 1100 Charles Street, where he died in 1803 at the age of 45. Although he has no tombstone in the Fredericksburg Masonic Cemetery, Gordon strongly believed he is buried there. He has not been forgotten, thanks to the local Surgeon Laurence Brooke Society, Children of the American Revolution, which was founded more than 50 years ago.

Notes:

This article originally appeared in a slightly different form as “Doctor’s Hours of Heroism” The Free Lance-Star, Town & County section. December 20, 2008. pg. 3, and is reprinted here with permission of the author and publisher.

“Image of the Fight aboard the Bon Homme Richard” comes from History of the United States, Volume 2 (of 6) by E. Benjamin Andrews (1912) Release Date: September 10, 2007 [EBook #22567]

"Laurence Brooke" may also appear in records as "Lawrence Brook," "Lawrence Brooks," and "Lawrence Brooke."