Now that the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Chancellorsville has passed, it seems a fitting time to look at how the lives of a family of mainly young women were affected by being suddenly thrust into a war zone and how they were able to survive with the aid of an enemy officer. Sue Chancellor was only fourteen when the area around her home became a bloody battlefield. Their house, called Chancellorsville, was used for a headquarters by first the Confederate and then the Union army while the family continued to live there.

In 1921, a monthly magazine called The Confederate Veteran (XXIX, no. 6, pp. 213-215) published, among its many stories, Sue Chancellor’s reminiscences of her wartime experiences. The house had been in the Chancellor family for generations and had been built to be used as an inn as well as accommodate the Chancellor family. It was well-placed for that purpose just off Plank Road--approximately modern-day Rt. 3 West from Fredericksburg--and served both well-heeled travelers on their way to the luxurious hot springs resorts in the west as well as teamsters carrying loads of goods and produce back and forth between the Shenandoah Valley and Fredericksburg.

Sue’s grandmother owned Chancellorsville in the years leading up to the War. Nearby was Sanford Chancellor’s house, Forest Hall, located near United States Ford, where her father had a bark mill. The Chancellor family saw changes in transportation that first came in the form of the Rappahannock Canal. The canal “ran by the side of the Rappahannock up from Fredericksburg,” bringing groceries, machinery, and dry goods and carried down bark and other produce by canal boat.

When Forest Hall was sold at her father’s death in 1860, young Sue, her widowed mother, and several siblings (George Sanford Chancellor; Mary Edwards Chancellor; Ann Elizabeth “Bettie” Chancellor; Jane Hall Chancellor; Frances Douglass “Fannie” Chancellor; Penelope Abbett “Abbie” Chancellor) moved to Chancellorsville. Sue’s first recollections of the War were of the Confederate pickets that were stationed nearby. The Chancellor family gave them meals, and the girls entertained them by playing the piano. The soldiers entertained the girls by teaching them how to play cards, though their mother did not approve.

Wartime meant a bit of relaxation of the rules. The soldiers were very cordial to the Chancellor family. Many of them were far from home and enjoyed showing small kindnesses. One young man, Thomas Lamar Stark, from Columbia, South Carolina, plucked a lamb from a herd of sheep that was being driven down the road for her to keep as a pet. She named it Lamar after the giver and kept it safe until Chancellorsville itself burned.

After the Battle of Fredericksburg, refugees came west from the town, and many stopped at Chancellorsville, where they received hospitality, though there were fewer to wait on them. As Sue wrote, after the Emancipation Proclamation “our servants ran away to the Yankees, who were, I think, not very far away in Stafford County.” So, when Confederate generals Anderson, Posey and Stuart rendezvoused at Chancellorsville, it was the Chancellor girls who made the supper and set the table. That supper was interrupted, however, by a courier whose dispatches reported that Union troops were crossing at the United States Ford. The men made haste to meet them but not before Stuart, well-known for his little courtesies to the ladies, gave Sue’s sister a small gold dollar as a fee to his waitress as well as a remembrance, according to Sue Chancellor's account.

Knowing the enemy troops were en route, the Chancellor women hid the silverware and Stuart’s gold piece in their hoop skirts. “A whole stock of hams, shoulders, and middlings” were already stashed under the front steps and the corn crop shelled and hidden under the beds. Sue remarked that “On the whole, the Yankees were kind and polite to us, but I can remember how they used to come in a sweeping gallop up the big road, with swords and sabers clashing, and how I would run and hide and pray. I reckon I prayed more and harder than ever I did before or since.”

The Federal troops made Chancellorsville into General Hooker’s headquarters. The Chancellor family and other refugees were ordered to stay in one room in the back of the house. The soldiers sent them food while the cannonade went on around them. Eventually, they were joined by fleeing neighbors until there were sixteen people in the one room.

On May 2, General Hooker ordered the civilians to be put in the basement as the fighting intensified. The house was full of wounded. The sitting room became an operating room, and the girls’ piano became an amputating table. At one juncture, a surgeon informed Sue’s mother that there were two wounded rebel soldiers in the house and she could attend them if she wished. She did.

The basement had flooded with water “over our shoetops” adding a layer of misery to the proceedings. A Union surgeon came down with a bottle of whiskey and instructions that they should all take some, and they were given food as well. But even a shot of whiskey couldn’t numb them to the reality of what was to come:

“It was late that day when the awful time began. Cannonading on all sides and such shrieks and groans, such commotion of all kinds! We thought that we were frightened before, but this was beyond everything and kept up until after dark. Upstairs they were bringing in the wounded, and we could hear their screams of pain. This was Jackson’s flank movement, but we did not know it then. Again we spent the night, sixteen of us, in that one room, the last night in the old house.”

“Early in the morning they came for us to go into the cellar, and in passing through the upper porch I saw how the chairs were riddled with bullets and the shattered columns which had fallen and injured General Hooker. O the horror of that day! The piles of legs and arms outside the sitting room window and rows and rows of dead bodies covered with canvas! The fighting was awful, and the frightened men crowded into the basement for protection from the deadly fire of the Confederates, but an officer came and ordered them out, commanding them not to intrude upon the terror-stricken women. Presently down the steps the san officer came precipitously and bade us get out at once, ‘for madam, the house is on fire, but I will see that you are protected and taken to a place of safety.’”

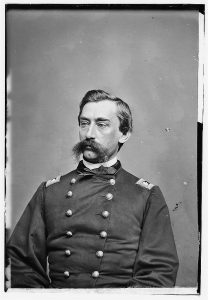

The officer who spoke to them was General Joseph Dickinson. As they moved out of the basement and into the light, the sight that greeted them was horrific:

“The woods around the house were a sheet of fire, the air was filled with shot and shell, horses were running, rearing, and screaming, the men a mass of confusion, moaning, cursing and praying. They were bringing the wounded out of the house, as it was on fire in several places.”

With General Dickinson leading them, they walked toward the United States Ford. After about half a mile, one of Sue’s sisters, who had been sick, had a hemorrhage in her lungs. General Dickinson stopped a soldier on horseback and demanded he get off and let the young lady ride, with the soldier walking next to her to support her. Another sister could walk no further and while they paused to rest, a Union officer rode up and demanded why General Dickinson was not at his duty post. Dickinson’s reply:

“If here is not the post of duty, looking after the safety of these helpless women and children, then I don’t know what you call duty.”

Dickinson escorted them to the pontoon bridge where he left them in the care of a chaplain who saw them safely over, an experience Sue Chancellor described as “wobbly.” Once on the other side, they were led to the top of a hill where the ailing sister fainted. A young drummer boy named Thacker brought ice and lemons and “tied up her head with his clean bandana handkerchief.... He said: ‘If this is “On to Richmond,” I want none of it. I would not like to see my mother and sister in such a fix.”

General Dickinson eventually sent an ambulance, and some of the party, including Sue were able to ride to Eagle Gold Mines in Stafford County. There, they were kept under guard for ten days and given good food and rest. The soldiers guarding them were kind, she said, and relieved “the irksomeness of our confinement” by conversing, playing cards, and having music. She thought there might even have been a bit of flirtation going on.

Chancellorsville was a victory for the Confederates, and the Chancellors were released on good terms with the captors. They could not go to their ruined home, so instead two of the girls became teachers in the Shenandoah Valley and Sue’s mother became matron at first the Midway and then the Delawan hospitals. Being still quite young, Sue was “put to school” in Charlottesville. Later on she would marry her Confederate veteran cousin, Vespasian Chancellor, and the couple came to live at 300 Caroline Street in Fredericksburg, a house with a troubled past.

Friendships forged in time of war can be life-long, even between those who should be enemies. The Chancellors never forgot General Dickinson’s kindness. He and Sue’s mother wrote to one another frequently and when he visited the battlefields he would always stop to see her. Indeed, he attended her funeral in 1892 out of “the affection he felt for her.”

General Dickinson was not the only Union officer to become happily reacquainted with the Chancellors. While taking the train from Fredericksburg to Philadelphia for the Centennial celebration in 1876, another passenger happened to overhear some of the family’s comments. Upon discovering that they were the Chancellors of Chancellorsville, he introduced, or, rather reintroduced himself. General Joseph Hooker shared the provisions of their brimming luncheon basket--but this time by invitation.

Sources

Chancellor, Sue. “Recollections.” The Confederate Veteran (XXIX, no. 6, pp. 213-215)

Available in numerous formats: PDF, EPUB, Kindle, Daisy, Full Text, DiVu, and Online. You will need to search for the story within the issue.

The Chancellors, Parts 1-3

http://spotsylvaniamemory.blogspot.com/2012_03_01_archive.html

http://spotsylvaniamemory.blogspot.com/2012/04/chancellors-part-2.html

http://spotsylvaniamemory.blogspot.com/2012/04/chancellors-part-3.html

Pat Sullivan has amassed very interesting research on the Chancellor family and their local connections. Includes many images of the family, their homes, and important papers.

These articles are available through the JSTOR database to CRRL card holders:

“The Chancellor Family”

Geo. Harrison Sanford King

The William and Mary Quarterly, Second Series, Vol. 15, No. 2 (Apr., 1935), pp. 178-198

Published by: Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture

Article Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1917093

A genealogy, with notes, of the Chancellor family. Most pertinent information on the Chancellorsville Chancellors begins on page 181.

“The Chancellors of Chancellorsville”

Ralph Happel

The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 71, No. 3 (Jul., 1963), pp. 259-277

Published by: Virginia Historical Society

Article Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4246953

Fascinating article has much information on the Chancellors during the Civil War and uses Sue Chancellor’s writing among its sources. Includes a full-color representation of the original Chancellorsville house, images of the Chancellors--including Sue, a map of the battle terrain, and quite a lot of background and details on the family and the times. There are even excerpts of sweet notes written in some of the girls' memory books by soldiers.

“Journey to the Springs, 1846”

William D. Hoyt, Jr.

The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 54, No. 2 (Apr., 1946), pp. 119-136

Published by: Virginia Historical Society

Article Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4245401

Jerome Napoleon Bonaparte, Jr., a relation of the Napoleon Bonaparte, passed through our area as a sixteen-year-old young man in 1846. He took a steamboat from Baltimore to Fredericksburg, and then an overland route to the famous White Sulphur Springs with the first stop at Chancellorsville. His account is rather detailed. Though there is not a lot about Chancellorsville per se, the description of travel in the area at that time is quite interesting.