By Kara Rockwell

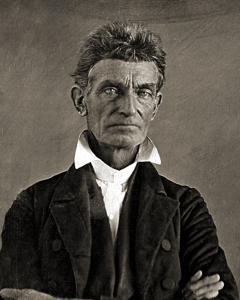

Born in 1800 to an abolitionist couple, John Brown was raised to believe that slavery was a sin and an insult to God. These beliefs influenced his actions throughout his life.

Brown spent years fighting for the abolition of slavery, including his fights against the Kansas Nebraska Act, which allowed settlers in those two territories to decide whether they would enter the Union as a "free state" or a state that permitted slavery. This act caused great tensions in the territories from both pro-slavery and anti-slavery settlers, which led to acts of violence on both sides. In May of 1856, Brown, along with several other men, attacked pro-slavery settlers along the Pottawatomie Creek in Kansas. Five settlers were killed. Brown left Kansas months later, fearing that he would be arrested for murder.

John Brown is probably best known for his assault on the town of Harpers Ferry, Virginia (now West Virginia). Brown’s plan was simple: he and his men would march into Harpers Ferry, take control of the federal armory there, and arm the enslaved people who would come to him. He believed this would start a rebellion of enslaved people throughout the South.

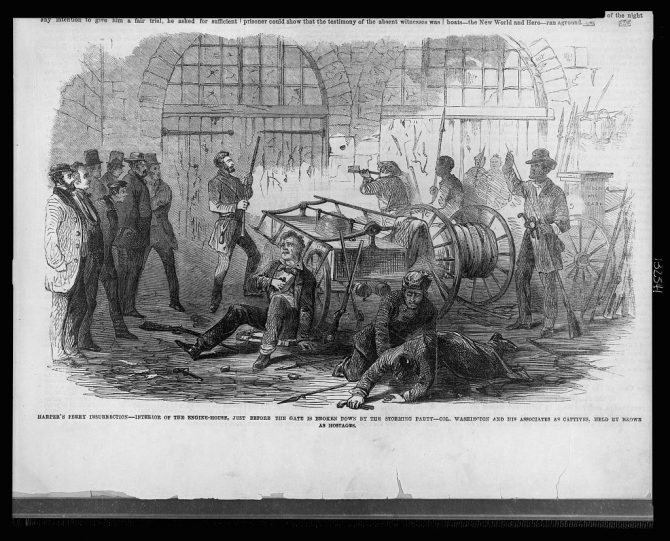

On the night of October 16, 1859, Brown and his men entered the town from Maryland, crossing over the Potomac River bridge. They cut the telegraph lines so that no warnings could be sent out, and several of Brown’s men were sent to guard the bridge over the Shenandoah River. First, Brown took control of the federal armory, which was guarded by only one night watchman, before proceeding to take control of Hall’s Rifle Works and then returning to the armory to establish a command post. He sent several men to take the prominent townsmen hostage, including Colonel Lewis Washington, son of George Washington's grand-nephew. Then, they waited for the enslaved people that Brown expected to join their cause.

Word of the raid leaked out to the town and the surrounding areas. The night watchman’s relief arrived and was shot at by Brown’s men. He survived, fled the scene, and warned the town about the armed men. In addition, a train traveling from Wheeling, Virginia (now West Virginia) to Baltimore was detained. When a free African American baggage handler, Heyward Shepherd, went to investigate, he was shot and killed by Brown’s men. The train was held for several hours and then was permitted to proceed. The conductor informed the authorities at other stops.

The next morning, Virginia militia units arrived and pushed Brown, his men, and the hostages back to a small fire engine house. Firing continued throughout the day as more militia units arrived. Then early the following morning, the United States Marines, under the command of Colonel Robert E. Lee arrived. Lee sent Lieutenant J.E.B. Stuart to order Brown’s unconditional surrender. When Brown refused, the attack on the fire engine house began. It was quickly over. Ten of Brown’s men were killed or critically wounded, and seven men escaped (although three runaways were later captured). Brown and four others were arrested.

Brown was arraigned on October 25, and his trial began on October 27 in Charles Town, Virginia (now West Virginia). On October 31, after 45 minutes of deliberation, the jury handed down a guilty verdict, and Brown was sentenced on November 2 to death by hanging. On December 2, Brown left the prison and traveled to the gallows by wagon, while sitting on his coffin. He handed a note to one of the guards which read:

“I, John Brown am quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with Blood. I had, as I now think, vainly flattered myself that without very much bloodshed, it might be done.”

Then Brown climbed the gallows and was hanged. His body was sent back to North Elba, New York, where he was buried.

Historians have long debated and continue to debate whether John Brown was a hero, a villain, or both. Learn more about Brown and his raid by exploring these resources.

Sources for the Introduction

Fiery Vision: The Life and Death of John Brown by Clinton Cox

New York: Scholastic Press, 1997.

The Trial of John Brown, Radical Abolitionist by James Tackach

San Diego, CA: Lucent Books, 1998.

In the Library:

Creating the John Brown Legend

Beck explores how Brown’s supporters affected his portrayal in history.

John Brown

Warren writes a readable narrative biography of Brown.

The Trial of John Brown, Radical Abolitionist

This book describes John Brown’s background, his actions at Harpers Ferry, and presents a concise description of the events of his trial and execution.

EBooks from EBSCO (available with your library card and a NetLibrary account):

On the Web:

The American Experience: John Brown’s Holy War

Created to accompany the PBS program, this site contains a transcript of the program, reference materials, and more.

Harpers Ferry National Historic Park

The official site of the national park, not only contains information for visitors, but also contains background on John Brown, the Civil War, and the town itself.

The Life and Trial of John Brown

Part of University of Missouri-Kansas City (UMKC) School Of Law professor Doug Linder’s Famous Trials web site, this site provides pictures, testimony and reports related to John Brown’s trial.

West Virginia Archives and History: John Brown

This site, created by the West Virginia Division of Culture and History, collects articles, documents, and more related to John Brown, his raid on Harpers Ferry, and his trial.