Beyond the I-95 Corridor

Drive out Route 17 north from Falmouth, past the strip malls, the shopping centers, and the subdivisions, and you’ll find that as the roadside gets less crowded, the scenery becomes more historic. In the 18th century, this corridor was more a place for pioneers than for fancy plantation owners, though there were a few of those, too. According to the book They Called Stafford Home, the oldest houses were mainly hewn of logs and did not survive into modern times. Between the natural aging process and the devastating Federal occupation during the Civil War, the Hartwood area saw and suffered through a lot of important history. It would take determined efforts in the late 20th century and beyond to preserve its place in the past and present it to future generations.

Tribal Times

Before the British settlers came, the area known as Hartwood—named for an old plantation—was a buffer region between the Potomac and Manahoac tribes. The Potomac was a relatively peaceful tribe with their main town of Petomek (“the place where the tribute is brought”) at what is now known as Marlborough Point. The Potomac tribe was part of a larger cultural group, the Algonquians of the Powhatan Confederacy. The Manahoac (also known as the Mahock) were of the Sioux-language culture.

Captain John Smith met a group of Manahoac above the falls of the Rappahannock in 1608 and reported that they lived in at least seven villages to the west of where he met them. By 1669, the Manahoac had been reduced in strength to 50 bowmen, possibly because of European-borne disease but also because of raids by their enemies the Iroquois. Eventually, the Manahoac joined up with other small tribes and moved further south. By 1728, they had disappeared as an independent group from the historic record.

Wagons, Ho!

Hartwood was originally part of King George County, but it was added to Stafford County in 1777 as part of a major redrawing of boundary lines. The region lay between the very active and profitable port of Falmouth and the bounty of the Shenandoah Valley. Prosperous farms that lay in the Valley, the Piedmont, and the Tidewater area usually had enslaved people of African descent to do the brunt of the work, as did mining operations.

Falmouth being a port along the Rappahannock’s Fall Line meant that tobacco, flour, and other commodities were carried down what is now Route 17 in wagons, either by the farmers themselves or by hired wagoners, to be traded for all manner of manufactured items arriving by ship from Europe and beyond which might be difficult or impossible for the western settlers to make for themselves.

At Allason’s store in Falmouth, one westerner named Philip Bush—the proprietor of “The Golden Buck” in Winchester—traded for fine Hyson tea, Tenerife wine, cloves, cinnamon, snuff, and writing paper, the last no doubt particularly useful as his clientele included George Washington. Another customer, Benjamin Berry, Jr., had more practical matters in mind: powder & shot, molasses, a hog-skin saddle, and bridle—but he also traded for an ivory comb, twelve pairs of plaid stockings and a yard of swanskin. Daniel Morgan was one of those far-traveling wagoners or teamsters whose record is noted in Allason’s logbook. The grandchild of Welsh immigrants, he would go on to become one of the American Revolution’s most famous generals.

A Tavern in the Wilderness

Naturally, along any well-traveled 18th- or 19th-century road there were taverns or ordinaries even in very rural areas. In Hartwood, travelers and teamsters could find food and lodging at Spotted Tavern. No longer standing, it was built of wood with three rooms on the first floor with separate entrances and two small rooms in the half-story, with white-washed interior walls, a large chimney, and wide plank floors.

In 1792, the proprietor failed to apply for his liquor license and got in a bit of legal trouble for it. Spotted Tavern was still standing during the Civil War, having served as a post office as well as a tavern from 1805 to 1825 and again in 1835, but by the Civil War, it was a private residence being used by the overseer’s family. According to a Works Progress Administration report, when the Union Army moved through the area, most of the enslaved people of Spotted Tavern Farm, who had suffered through years of cruel overseers, made their escape.

Hard Use for Houses of Worship

As America realized her independence, part of what followed was religious freedom and the chance to worship as one chose. Originally, Anglican worshippers attended a “Chapel of Ease” called Yellow Chapel for poplar wood’s color that was part of King George County’s Brunswick Parish. By 1825, the little church was in use by the Presbyterians who eventually built a brick church nearby, circa 1858. During the Civil War, Hartwood Presbyterian Church was a point of contention between the two sides.

In November 1862, Union Captain George Johnson and his troops were surprised at the Presbyterian Church by General Wade Hamilton's Confederate cavalry, who took many prisoners. Earlier, Captain Johnson’s men had burned the woodwork and the pews and, fancying himself something of an artist, Johnson started to draw on the walls of the church, ignoring the warnings of an upcoming attack. His artistic yen ultimately cost him, for he was dismissed for “disgraceful and un-officer-like conduct.” After the War, the parishioners raised the money to not only restore the church but also to add modern improvements.

Mount Olive Baptist Church, founded May 16, 1818, is believed to be the oldest African American church in Stafford County. From five farmers and a preacher, it has grown to a congregation of approximately 350 people and is still expanding. During the Civil War, it was a log structure but has since been replaced by a brick building.

“The Mud March” through Hartwood and Other Civil War Happenings

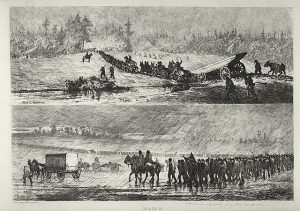

There were numerous skirmishes and troop movements in this part of Stafford County during the Civil War, but one of the most memorable was surely “The Mud March.” In January of 1863, Union General Burnside ordered his three Grand Divisions to march up the north side of the Rappahannock to Banks Ford and U.S. Ford with the idea of crossing to attack Fredericksburg—again. The weather defeated him. On January 20, “a violent rain-storm set in, making the roads impassable for artillery and wagon trains.” An officer put in a request for “50 men, 25 feet high, to work in mud 18 feet deep.”

After enduring two more days of rain, General Burnside gave up and ordered his troops back to camp. It was one of the most humiliating and miserable experiences the Union Army faced. The drenching misery was captured in a battle sketch by Alfred R. Waud entitled, “Winter Campaigning.” Burnside lost his command on January 26 to General Joseph Hooker.

Less than a month later, on February 25, Confederate commander Fitzhugh Lee—Robert E. Lee’s nephew—used cavalry charges to inflict casualties and take approximately 150 Union soldiers prisoner from their picket line at Hartwood Church. As one Northern observer noted, “considering the [poor] conditions of the roads, [the Federals] made very good time to the rear.” Newly-appointed General Hooker was livid and became even more determined to reform the Union cavalry:

“We ought to be invincible, and by God, sir, we shall be! You have got to stop these disgraceful cavalry ‘surprises.’ I’ll have no more of them. I give you full power over your officers, to arrest, cashier, shoot—whatever you will—only you must stop these surprises. And by God, sir, if you don’t do it, I give you fair notice, I will relieve the whole of you and take command of the cavalry myself.”

The Union Cavalry did do rather better at Kelly’s Ford in March. Although General Hooker lost at the Battle of Chancellorsville in late April and early May of 1863, he is credited with greatly strengthening the Union cavalry. The lesson learned at Hartwood Church carried over to the rest of the war.

It is certain the ordinary Union soldiers’ lives were dreary during those many months, but they tried to entertain themselves, as a letter John Marshall Brown of Portland, Maine, to his sister Ellen (Nellie) from a camp in Hartwood (November 21, 1862) tells:

“…it rained all night & nearly all day-to-day. It has cleared up at last, though, and tomorrow we move. If you could have peeped into our “dining room” last night after night supper you would have seen a queer sight all of us were sitting around the table telling ghost stories until late in the night. It was raining great guns & we had to do something to pass away the time & with the mud an inch deep on the floor of the tent you can imagine that we were thankful at being able to keep ‘jolly.’”

On a more significant note, the arrival and occupation of U.S. troops were welcomed by the vast majority of the area’s enslaved people, who put down their work and made their way to freedom.

The Hartwood Houses

Hartwood House was built between 1800 and 1825 by Irish immigrant William Irving. Originally part of a 5,000-acre plantation, it is estimated that William Irving owned between 100 and 125 enslaved people of African descent for field work as well as domestic duties, as the basement kitchen was connected by tunnels to the quarters for enslaved people. This Federal-style house was used during the Civil War as a headquarters by both Union and Confederate forces, and the barn served as a Confederate hospital. Both the house’s and the barn’s existences were threatened by a road-widening project in 1972, but Governor Linwood Holton intervened on behalf of the Historic Falmouth Foundation and the Virginia Landmarks Commission to prevent its destruction. Today, it has been restored and modernized and serves as a venue for wedding receptions and other special events.

Hartwood Manor, on the other hand, is built in a Gothic Revival-style, with twin gables and an English basement and is set on a 695-acre farm. It was built by Ariel and Julia Foote in the 1830s. The Footes came to Stafford County as newlyweds from Connecticut, which may explain why the house was done in a style popular in New England but relatively rare in Virginia. Its bricks are believed to have been made by the plantation’s enslaved people on site. During the Civil War, it, too, saw action as a Union hospital. Today, it is the home to Hartwood Roses, an educational demonstration garden specializing in rare and historic varieties.

Modern Times

As Stafford became a popular bedroom community for D.C., it was inevitable that developers would start to eye rural and historic land. Dr. H. Stewart Jones, affectionately known as “Stewart,” helped form the Citizens to Serve Stafford to be a voice for preservation. She was also a founding member of the Historic Falmouth Towne and Stafford Inc., a forerunner of the Stafford County Historical Society.

In the early 1990s, Citizens to Serve Stafford helped clean up Hartwood Baptist Meeting House’s neglected cemetery with the help of the Boy Scouts. They also saved “the little red barn” that was on the site of a planned elementary school. Thanks to the efforts of local preservation groups, Stewart’s dream of the Hartwood Historic District has been realized. It includes five specific buildings: H. Stewart Jones's home at 35 Hartwood Church Road; Hartwood Presbyterian Church; the community's original post office building, now a private home; the little red barn, symbolizing the area's rural roots; and the Meeting House Cemetery. This area is also part of the Civil War Trails program.

Wine, Roses, and Gold

Whether you prefer following in the footsteps of history or taking in recreational activities, this largely undeveloped area of Stafford County has many treasures to offer.

Although the Hartwood area is awash in history, there are many other reasons a person might care to visit. Curtis Memorial Park—a county park—has boating, fishing, golfing, concessions, a skateboard park, walking & hiking trails, an outdoor pool, picnic shelters, an amphitheater, and more.

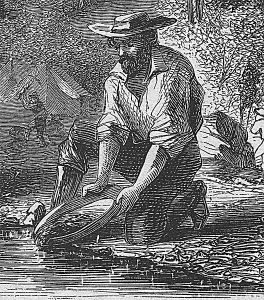

Today, Hartwood Winery, located on Hartwood Road, offers tastings and special events throughout the year. Hartwood Roses is an educational garden that contains more than 800 different varieties of roses, with special emphasis on rare and historic varieties, and popular classics that are well-suited for modern gardens. North of Hartwood lies Goldvein, and, indeed, a gold vein runs through the Rappahannock region and was profitably mined until the California Gold Rush. You and your family can still get a taste for the glimmering history at the nearby Gold Mining Camp Museum at Monroe Park, not very far over the Stafford County line.

Books

The Church on the Hill A History of Hartwood Presbyterian by George D. Taylor

Oral History with Dr. H. Stewart Jones

Stafford County by Anita L. Dodd

They Called Stafford Home: The Development of Stafford County, Virginia, from 1600 until 1865 by Jerrilynn Eby

The Union Cavalry Comes of Age: Hartwood Church to Brandy Station, 1863 by Eric J. Wittenberg

Articles from the Library’s JSTOR Database

“Falmouth and the Shenandoah: Trade before the Revolution”

Miles S. Malone

The American Historical Review, Vol. 40, No. 4 (Jul., 1935), pp. 693-703

Published by: Oxford University Press on behalf of the American Historical Association

Article Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1842420

“The Indian Inhabitants of the Valley of Virginia”

David I. Bushnell, Jr.

The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 34, No. 4 (Oct., 1926), pp. 295-298

Published by: Virginia Historical Society

Article Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4244104

‘Stafford County Post Offices’ in “Virginia Post Offices, 1798-1859”

Author(s): Virginius Cornick Hall, Jr.

Source: The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 81, No. 1 (Jan., 1973), pp. 49-97

Published by: Virginia Historical Society

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4247768

These Articles Appeared in The Free Lance-Star Newspaper

If no link is given, ask a librarian about access.

“158-year-old Manor House Is Feeling New Life” (4/22/2006)

"Church to Dedicate Historical Marker" (1/5/2005)

“Finest Materials They Could Find:” Payne House in Hartwood Contains Several Uncommon Features

http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1298&dat=19941110&id=8OcyAAAAIBAJ&sjid=uwcGAAAAIBAJ&pg=5469,1891623

"Historic Hartwood House has been landmark for nearly 200 years" (12/8/2006)

“Mount Olive Set to Expand Again” (5/16/2009)

"Stafford Mourns ‘Stewart’" (4/21/2009)

More Online Resources

A Challenge Answered: The Battle of Kelly's Ford - March 17, 1863

https://emergingcivilwar.com/2013/03/17/a-challenge-answered-the-battle-of-kellys-ford-march-17-1863/

Friends of Stafford’s Civil War Sites

http://www.fscws.org/

Hartwood Presbyterian Church

http://hartwoodpresbyterian.com/

Historic Markers Database

http://www.hmdb.org/

John Marshall Brown letter from Hartwood, Va., 1862

http://www.mainememory.net/artifact/25211

National Register of Historic Places: Hartwood Manor

https://www.dhr.virginia.gov/historic-registers/089-0021/

Rappahannock Valley Civil War Round Table: Stafford County Driving Tour

http://www.rvcwrt.org/stafford.html

Richland Baptist Church

https://www.richlandbaptist.com/

The Stafford County Historical Society

http://www.staffordcountyhistoricalsociety.org/

Photo of the medical tent exhibit appears courtesy of the Hartwood Days Festival.