By the Fredericksburg Area Tourism Department

In 1714, the Stuart dynasty ended in England with the death of Queen Anne. George I, elector of Hanover, Germany, was selected to become the next ruler of England, thus beginning the long reign of the House of Hanover.

Hanover Street, named after the House of Hanover, was developed on part of a tract of land granted in 1671 to early Virginia settlers Thomas Royston and John Buckner. The street was one of Fredericksburg's original eight streets when the city was granted its charter in 1728.

Buckner's half of the land was sold in 1735 to Henry Willis. Willis died soon afterward, and the executors of his estate divided the land, including what is now Hanover Street, into lots. Part of this land was eventually sold to John Allan, a Fredericksburg land developer. Allan proceeded to develop a community called Allan Town. In the latter part of the century, Charles Yates, a Fredericksburg businessman, acquired almost all of the land in Allan Town.

In 1809, Daniel Grinnan, an early 19th-century merchant and land developer, bought a section of Allan Town from the estate of Charles Yates, who had died earlier that year. At that time, only a few houses existed on Hanover Street. One, which had been Yates' house, was built in the path of Charles Street, preventing the street from continuing on toward Charlotte Street.

In 1815, Grinnan and Thomas Reade Rootes, at that time owner of Federal Hill, joined together in the development of their land. They employed John Goolrick to survey the property and had the streets and lots marked off. Sales were slow at first, but, by the middle of the century, most of the lots had been bought and houses erected.

By the time of the Civil War, Hanover Street had established itself as an attractive residential area. Its large houses were owned by prominent citizens - doctors, lawyers, the mayor, and members of the city council.

Many Hanover Street families vacated their homes during the Civil War. On December 13, 1862, the Federal Army of the Potomac, under the command of General Ambrose E. Burnside, marched from the river, up Hanover Street and past its stately homes in an assault on the Confederates' position on Marye's Heights. After the war, the residents returned to find their homes livable but scarred by battle.

By the turn of the century, more new buildings had been constructed, and many of the original homes had been remodeled to keep up with architectural fashions of the day. The neighborhood in the early 1900s was still a homogenous one of prominent citizens. On summer evenings, the residents sat out on their front porches and watched the world go by.

Today, the quiet tree-lined street reflects the layers of time. The architectural styles and periods are still evident, and the character of the street has been preserved through careful restoration.

301/303 Hanover

301/303 Hanover

This pair of late Georgian/Federal houses were built c. 1830, and at one time 301 was "The Ivy Motor Inn," a small inn for travelers. The brickwork on this structure is laid in Flemish bond, a form of brick construction in which bricks are placed alternatingly lengthwise and widthwise. Notice the broad classical models in the panels of the reveals around the doors, and the decorative transom pattern above the door at 301. The sills of both doors are dressed sandstone, probably Rappahannock sandstone.

307/309 Hanover

307/309 Hanover

In 1816, Dr.James Carmichael, from Glasgow, Scotland, bought the main house, 309, from Charles Yates, a prominent Fredericksburg merchant who had built it in the 1780s. In 1820, Dr. Carmichael built the small brick office, 307, for his "medicine shop." Five Carmichael doctors in four generations treated Fredericksburg residents here.

Dr. James Carmichael, a well-respected doctor, was a character who loved practical jokes. On one memorable occasion, he and a co-conspirator sprinkled snuff over the heads of some worshippers at the Methodist Church across from his house. The two jokers fled as the congregation erupted in sneezes but were apprehended and spent the night in jail. Note the trim boards on the ends of the eaves on either side of 307, and the porch of 309, carefully shaped to match moldings in the cornice. Also note the pattern of the transom in 309, copied in the pattern of the porch's railing. The chimneys are set back so that the top section of the stack stands free of the structure and roof of the house, possibly to reduce the risk of fire.

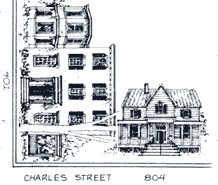

804 Charles Street

804 Charles Street

Mrs. Elizabeth Thornton Fitzgerald, wife of James Henderson Fitzgerald, built this Gothic Revival style house in 1866. In 1983, this house, originally located at 408 George St., was almost torn down to make way for an expansion of the Fredericksburg Saving and Loan Association. In 1984, after the plans for destruction were protested by the Historic Fredericksburg Foundation, local developer Hunter Greenlaw bought the house and moved it to its present site, where the home was completely restored. It now contains a law office. Notice the fleur-de-lis pattern carved on the porch banisters and gables. Note also the stylized Italianate pattern of the porch columns and the full-front American porch, typical of the 1860s and later.

401 Hanover

401 Hanover

This house, originally two stories high, was built in l851 by Eustace Conway, a successful businessman. During the Civil War, this was the home of the war-time mayor, Montgomery Slaughter. Around 1900, St. George FitzHugh, Commonwealth's Attorney of Fredericksburg, lived here and hosted a reception for President William McKinley, who was attending a reunion of the Society of the Army of the Potomac, the first time such a reunion was held on Southern soil. In 1927, Dr. J. Minor Holloway, a prominent physician, bought the house and had his medical office in the basement. The house remained a single-family home until 1984 when the sturdy 27-room building was converted into five apartments and two business offices. Note the differences in the brickwork where the original two-story structure was raised to three in 1902 by Fitzhugh. Notice also the bold scroll ornaments above the first-floor window moldings that echo the bold scrolls of the stair railings, carved in natural stone.

403 Hanover

Built in 1826, this was the home of the Rev. John Kobler, a retired Methodist minister from Culpeper, Virginia. He and his wife, Mary, lived here until they moved to 405 next door. The Koblers willed 403 to the trustees of the Fredericksburg Methodist Church to be "held as a parsonage or otherwise," and it still serves as the parsonage for the Methodist Church. The toothy stucco is a 20th-century cladding, probably covering a frame structure.

4 05 Hanover

05 Hanover

Daniel Grinnan, one of Fredericksburg's early 19th-century merchants and developers, built this two-story brick house in 1821. In 1830, he sold it to the Rev. and Mrs. John Kobler, who had been living in the house next door, 403. Upon Mrs. Kobler's death in 1855, 405 was left to the Missionary Fund of the Methodist Church. The house became known as the "Missionary House," and profits from its rent went to the Methodist Missionary Fund in New York. In 1873, the "Missionary House" was sold and has been privately owned since. Note the Flemish bond brickwork, and the bricks stepping out one above the other to match the simple pattern of the cornice. The porch was added between 1900 and 1920.

407/409 Hanover

407/409 Hanover

This handsome pair of Greek Revival townhouses was built in 1844 by Robert C. Bruce. Mrs. John J. Young lived in 409 during the Civil War and said in a W.P.A. project report that Yankee soldiers would come there for water. They were very friendly, and she would let them come in the back and wash their hands, but "I had seven daughters and was most careful to lock them upstairs." The transom pattern shows evidence of remodeling c. 1900. Note that the double structure shares chimneys.

501 Hanover

501 Hanover

Underneath this elaborate c. 1900 exterior is an early 19th-century house. Around 1819, Judge John Tayloe Lomax built a simple two-story brick house on what was then the outskirts of town. Lomax, a lawyer, in 1820 became the first professor of law at the newly formed University of Virginia in Charlottesville. Lomax conducted a law school in the basement of this house. Before the Civil War, he is said to have wept as he cast his vote in favor of the secession and said, "To think that I have survived the nation!" He died on October 1, 1862.

Judge Alvin T. Embrey, a successful attorney before his judicial service, bought the house in 1900 and made the additions c. 1908, including the Classical Revival porch and rear wing, which almost doubles the size of the house. Notice the bricks in the added bay window on the front porch. They are thinner and laid in American/Common bond, unlike the Flemish bond of the rest of the porch. Notice also the interesting use of concrete with added color and texture that gives a brownstone character to the fence along Prince Edward Street.

501 1/2 Hanover

501 1/2 Hanover

This building was the kitchen of the original Lomax house at 501 Hanover St. Judge Embrey and his family lived here during the remodeling of 501. A rear wing was added to this house c.1902. A seam along the side of the building shows where the front was extended, possibly to make it even with the front of 501. Note the two kinds of shingles on the roof and the decorative wood carvings on the eaves.

503 Hanover

503 Hanover

This house was built prior to 1891 and remodeled about 1903 by owner Vivian Minor Fleming. In 1922, Mrs. Fleming, with the help of her daughter, Mrs. Horace H. Smith, formed the Kenmore Association to raise money to buy Fielding Lewis' plantation home, Kenmore, and restore it. Mrs. Smith, who lived at 503, was known to the town as "Miss Annie," and to many, her name is synonymous with Kenmore. Miss Annie was an energetic presence in the community. From 1922 to 1952, she devoted her time and efforts to publicizing and raising money for Kenmore. A determined and tireless saleswoman, Miss Annie raised, by various creative means, roughly $750,000 for the Kenmore Association. Very few people in the city were not familiar with Miss Annie or had not been recruited by her at some point to help "Save Kenmore." She lived by her motto, "Praise the Lord, work like the Devil, and love Kenmore." In 1949, she was named First Lady of Fredericksburg for her efforts in developing the city's tourist trade. She died in 1962 in this house. Notice the angled lower bay added to the left of the house and the shallow bay window in the third-floor gable. The splendid details show the architectural ferment that was going on in American in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

"Federal Hill"

"Federal Hill"

This late Georgian style house with Federal details was built c. 1792 by Robert Brooke, governor of Virginia from 1794-1796. He named his home "Federal Hill" after the Federalist Party which he helped found. The house was built before the present-day street, which explains its angular orientation. Brooke's sister, Elizabeth, and her husband Fountaine Maury, mayor of Fredericksburg in 1793, lived here from 1794 until 1801 when the house was sold to Thomas Reade Rootes, a local lawyer. During the Civil War, the house was used as a field hospital by the Army of the Potomac. Confederate Major General Thomas R. R. Cobb, grandson of Thomas Reade Rootes, was killed defending the Sunken Road at the battle of Fredericksburg on December 13, I862. The shot that killed him is said to have been fired from a cannon located at Federal Hill, where he visited as a child. The exposed brick chimney is a traditional method of construction. The hottest part of the chimney is not against the house, perhaps for reasons of fire prevention. Notice the holes in the chimney, scars from the Civil War. Attempts were seldom made to repair such damage; cannon shots in the bricks were considered to be sacred wounds. Note the wonderful wrought-iron work in the fences.

Fredericksburg Pentecostal Church

Fredericksburg Pentecostal Church

This church, originally Trinity Episcopal Church, was first formed by members who withdrew from St. George's Episcopal Church on Princess Anne Street. In 1877, the Rev. Dr. E. C. Murdaugh resigned his post as minister of St. George's for a difference of opinion with some of the congregation. Members of St. George's who supported Murdaugh organized Trinity and made him Rector. The congregation rented church space from the Methodist Church until this building was completed in 1881. The Pentecostal Church has been worshipping here since 1959 when the Trinity congregation built a new church on College Avenue. The stained glass windows that are now in the College Avenue church were moved from this building. This structure is a dramatic concoction of slate, stone, wood, and stucco. Much of the original detail is still intact. Note the different color patterning in the slate of the roof.

408 Hanover

408 Hanover

Built c. 1840, this Greek Revival house was vacated during the Civil War, a time that saw troops marching past its front door and left a cannonball embedded in its upstairs wall. The house was first occupied by the Green family in 1867 and has remained in the same family since that time. The house has recently been restored. Note the fine Flemish bond brickwork; the high quality of the brick, and the even joints of the bricklaying. Note also the fluted Greek Doric columns and the long bay windows on the first floor.

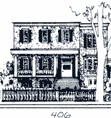

406 Hanover

406 Hanover

Built in 1853, this Greek Revival house was originally intended to be the Presbyterian Manse, but the church trustees sold it in 1854 to George B. Scott, a Fredericksburg businessman. John G. Hurkamp, a German immigrant and a tanner by trade, bought the house in 1862. Hurkamp was the first to use American sumac in the tanning process and won an award for that use at a Paris Exposition. He owned a tannery and an iron foundry in Fredericksburg.

Federal Major General John Sedgwick had his headquarters in this house during the Civil War in 1864, and Hurkamp, although a Confederate sympathizer, treated the general and his staff with kindness. General Sedgwick wrote a letter of thanks to Hurkamp, saying he hoped to someday return the favor. A few months later, in retaliation for the arrest of some Federal stragglers in Fredericksburg, 56 Fredericksburg citizens were arrested and taken to military prison at Fort Delaware, an island in the Delaware River. Hurkamp, one of the prisoners, showed Sedgwick's letter and received an immediate release from President Lincoln. The others were held some two months.

City Park, located at the corner of William Street and Prince Edward Street, was named Hurkamp Park in 1881 when Hurkamp donated a wrought iron gate and build a fence around the area to keep the pigs out. It has been known as City Park since the 1930s, although recent efforts have been made to restore the park's original name. Note the ironwork on the fence, made at Hurkamp's iron foundry. His name is set in the gate. The porch was added by Hurkamp after the war.

404 Hanover

404 Hanover

Built c.1842 by Dr. Richard Carmichael, this house was bought by Dr. George Chewning, a Fredericksburg dentist, in 1888. In 1894, Vice President Adlai Stevenson and his wife stayed here when President Grover Cleveland and his cabinet came to Fredericksburg to dedicate the Mary Washington Monument. Note the handsome wooden window hoods that give the house an Italianate architectural character. The brickwork is of the same high quality as 406 and 408. Note how the wing with the bay window addition closely resembles the addition on 401 across the street.

402 Hanover

402 Hanover

Built in 1888 by Dr. George Chewning, this French Second Empire style house was bought in 1910 by Dr. Robert Payne, a popular Fredericksburg physician. The side apartment was used by Dr. Payne as his medical office. Dr. Payne died in 1944 and willed the house to his daughter, who divided it into apartments. It was sold in 1977 and returned to a single family home except for Dr. Payne's office which remains a small apartment. Note the mansard roof, characteristic of the Second Empire period. Note also the bold moldings along the eaves and at the break in the roof. The roof is covered with patterned metal, made to resemble shingling, a style of the late 1800's that is now highly prized by lovers of that period.

400 Hanover

400 Hanover

This big Colonial Revival house, built about 1900, is a "suburban" contrast to the townhouse next door at 310. The shingle texture is echoed in the landscape by the cobblestone texture of the driveway, which is a reminder of the various kinds of brick, stone and dirt pavings of the streets and sidewalks throughout the years. The Methodist Church bought this house in 1955 and now uses it as Sunday School space. Note the dormer windows and big wrap-around porch.

310 Hanover

310 Hanover

A house existed on this site as early as 1843 when the land was owned by the Helen Grinnan Estate. This home probably was demolished and replaced by the two-story brick house which was on this lot when it was sold in 1890 to Celia Goolrick. Elizabeth Pittman bought the house in 1897 and completely renovated it around 1898. It was probably at that time that Colonial Revival swags were added to the porch. The Methodist Church bought the building in 1958, and it is used as part of the church today. Steam-operated machinery was used to press the clay to make the very hard, very even bricks of the facade. The mortar joints, referred to as "buttered", are so called because they are spread thin, like butter. Notice the heavier, simpler brickwork of the basic structure behind the facade.

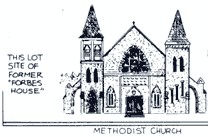

The Methodist Church

The Methodist Church

In 1840, the Board of Trustees of the Methodist Church purchased this lot. The Rev. John Kobler, a man who is said to have done more for the Methodist Church in Fredericksburg in his time than any other person, raised money almost single-handedly for the building. The original building here was completed c. 1841. Kobler died in 1843 and was buried beneath the pulpit. About 1844, differences in opinion regarding slavery became so strong within the church that the congregation split. In 1848, the Southern Methodists, in favor of slavery, withdrew to worship at City Hall and later at a church built on George Street. The Northern Methodists, opposed to slavery, remained at Hanover Street. After the war, the two factions were reunited. In 1879, the church on Hanover Street was torn down to make way for a new one. The present church was completed about 1882. In 1963, this became the first Methodist church in the Virginia Conference to accept blacks into its congregation. The church is an example of Victorian Gothic style. Note the high-quality brickwork, including bricks that have been specially cast into shapes to make the molding around the wing. Also notice the creative use of straight brief in the facade, the pyramids and half sphere patterns, elegant ironwork.

"Forbes' House"

A large frame Federal style house with large exterior chimneys was built on this site c.1786. It may have been the original house of Charles Yates who owned the property at that time. The house was sold to Frank Thornton Forbes in 1871 and was known as the "Forbes House" until the middle of this century. The once elegant house, which had been neglected, was torn down soon after the property was bought by the Methodist Church in 1961. The church has recently revitalized plans to build an expansion on this lot.

Allan Town

In 1759, John Allan, an early Fredericksburg land-developer, merchant, and town trustee, bought from William Hunter ten acres of land, extending from what is now Charles Street westward. Allan divided this plot into two rows of four lots each and divided the rows by a street called Allan Street. The area, at that time outside the Fredericksburg city limits, became known as Allan Town. Its streets and lots were laid out parallel to the existing boundary lines agreed on by landowners Henry Willis and John Royster in 1735, thereby putting them at an angle to the other Fredericksburg streets.

In 1759, Fredericksburg expanded for the first time, and Allan Town was included within its boundaries. In 1763, Charles Yates, Fredericksburg businessman and landowner, purchased two lots in Allan Town. In 1783, Yates asked City Council whether or not his property was within the city limits and if he should pay taxes to Fredericksburg city or to Spotsylvania County. The council, for unknown reasons, could not decide on an answer and delayed collection of his taxes. Yates continued to pay taxes to Spotsylvania, and the issue was forgotten for the time. In 1850, 67 years after Yates' original question, the city council made a final decision to collect property taxes from the residents of Allan Town.

Research and text by Kathy Adams. Architectural notes by John C. Pearce.