Source: The William and Mary Quarterly, Vol. 27, No. 4 (Apr., 1919), pp. 248-257. Parts I and II may also be read online.

FREDERICKSBURG IN REVOLUTIONARY DAYS

(Concluded)

PART III.

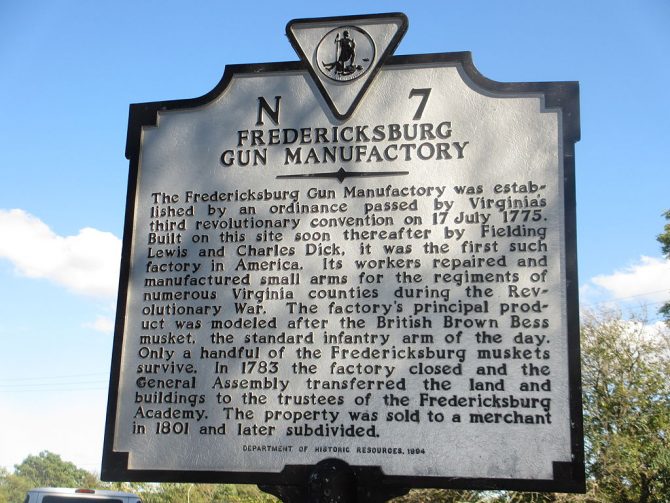

We come now to the record of one of the most important of Virginia's institutions for the prosecution of the war: the manufactory of small arms established by ordinance of the Convention of July, 1775. The facts here presented are those discovered in files of correspondence at present in the Department of Archives of the Virginia State Library, Richmond. There are large gaps in the record of this manufactory: the books and papers of the director seem to have wholly disappeared, and we are forced to rely on the ordinance of Convention establishing this institution, a few subsequent laws and single documents for its history prior to September, 1780; but, from that time forward there remains the correspondence of Charles Dick, on whose shoulders rested the burden of keeping up this institution.

The ordinance of the convention of July, 1775,1 establishing this manufactory of arms provided Fredericksburg as its location, named Fielding Lewis, Chas. Dick, Mann Page, Jr., William Fitzhugh, and Samuel Selden or any three of them as commissioners to execute the ordinance; directed the employment of a sufficient number of artificers to manufacture such arms as should be directed from time to time by committee of safety and to continue the work "so long as the necessities of this colony shall require." An initial appropriation was made £2,500 (a sum having at that time about the purchasing value of 15,000 to 20,000 dollars of present day currency), and it was also directed that such other sums as the Committee of Safety from time to time direct should be paid by the State's treasurer. The commissioners were to give security on receipt of the sum and were directed to transmit to the committee, from time to time, accounts of the state and progress of the manufactory and its work.

Whatever may have been the offices performed for the institution by Fitzhugh, Page and Selden, their connection with the manufactory must have been short lived for in a memorandum for the executive made in 1781 (Appendix 8) Chas. Dick alluded to his and Colonel Lewis' connection with the work as though they had accomplished the whole undertaking, and quite certain it is that no record has so far been discovered which mentions Fitzhugh, Page or Selden as having any connection with the work other than the ordinance for establishment. Mr. Dick says that he and Colonel Lewis accomplished the establishment of the factory during the first year "after much trouble and attention" and succeeded in putting it "on an extraordinary good footing." The commissioners purchased from Richard Brooke very soon after the ordinance was passed a tract adjoining the town of Fredericksburg and thereon erected the necessary buildings.

The date of the factory's completion is not positively known but must have been some time early in 1776. The magazine (which was not under direction of the commissioners) a substantial stone building which stood "just by" the factory, though begun in 1776 was not completed until about the latter part of 1781. There is still in existence a contemporaneous copy of the bill for materials used in the construction of and for work done on the magazine (Appendix 9). For use of the factory the commissioners also leased from Mrs. Lucy Dixon (the widow of Roger Dixon, who was for years a wealthy and influential resident of the town), a mill house on Hazel Run which they converted to the use of grinding bayonets and ramrods.

It was intended by the commissioners to have always resident a master workman whose duty it was to examine the work, to receive it, to correct faults, to instruct the ignorant, to issue tools and provisions and to look after everything; and in addition, says Mr. Dick, "when at leisure works." This of course is a familiar paradox of trade. In October, 1777, by legislative enactment the commissioners were instructed to receive apprentices. There are no extant reports to show the actual extent of the work monthly or annually accomplished by the factory but in September, 1781, Mr. Dick seemed to think that under auspicious circumstances a hundred stand of arms a month might at least be turned out. In addition to this there was a great amount of repairing to be done to damaged arms.

In October, 1782, Mr. Dick in outlining to the Commissioner of War a plan for further work at the factory estimated the running expenses at £2,958 a year. This included the master workman's pay, the pay for thirty workmen, negroes to do the drudgery, rent of the Dixon mill place, and "a stock to work upon." The system on which the gun factory was run, as outlined by Mr. Dick in a communication in 1782 addressed, presumably, to the governor, was indeed ideal from the manufacturer's point of view.

"When breakfast and dinner are ready the bell rings and all regularly sit down at table to eat, when done, to work again, so that no time is lost, when absent they [the men] are duly charged with lost time. There is a spacious garden which supplies necessary greens and roots and a noble spring for water. By above method order and government with sundry rules too tedious to mention and the greatest economy the factory has been carried on to this day to great advantage to the State."

The concluding "Has been carried on to this day," justifies one in assuming that this had been the system from the beginning of the work. Reference was made above to an estimate made by Mr. Dick for running the factory under normal conditions. But the most remarkable part of the whole proceeding seems to have been the fact that Colonel Lewis and Mr. Dick managed to run the institution--this vitally important part of the State's work--under the abnormal conditions of a deranged treasury. The initial appropriation was turned over to them and probably the government met some of the later demands but marked depreciation had occurred in the currency by 1778 and funds became very difficult to procure.

The gun factory's existence was dependent on funds and deeply sensible of the importance of the institution the burthen of the commissioners' correspondence with the executive was for the necessary funds to carry on the work. Discouraging indeed and almost heart-breaking must have been the commissioners' knowledge of the discrepancy between the necessity for the work to continue and the amount of the funds available therefor. But patriots to the core, these men--Fielding Lewis and Charles Dick--threw themselves into the breach and tried to the uttermost to save the work to the State. Underpaid--and most frequently unpaid--for their personal services, which were incalculably valuable, these men staked their personal credit to save the gun factory.

In the only extant letter of Fielding Lewis' relative to the manufactory which has been so far discovered, he tells the then treasurer of the State, under date of Feb. 9, 1781 (Appendix 10), that but for his advances in money, the most part made as early as the preceding July, that "the factory must have been discontinued, as no money could be had at the treasury or, so little, that the business must have suffered." And furthermore he frankly says, "had I suffered that factory to have stopped I know the public would have condemned me for it, altho I should not have been blamed as the cause would have been the want of money."

He had been requested to borrow for the use of the State all the money that he could; he says that he thinks he promised to raise between 30,000 and 40,000 pounds, "seven thousand of which" (about $50,000) says he, "I lent the State being all that I had at that time on hand." And now, having greatly distressed himself, impoverished, unable (by his own admission) to pay even his taxes or conduct his business in the usual manner, he appealed for what was only due him, and he may not be blamed for a parting shot, nor held as one with motives merely mercenary (as many a carping critic would blame and hold him) when he closes his appeal with: "Can it be expected that the State can be well served when its best friends are used in the manner I have been treated."

It is a self evident proposition that a State owes to its citizens, even in such trying times, the same honest, straightforward treatment that the citizen owes to the State. A knowledge of Fielding Lewis' interest in the manufactory of arms and the strenuous efforts made by him to assure its successful operation pronounces this no vain boast, but the declaration of a clear conscience and a wounded heart. Towards the autumn of this year there was a marked decline in Colonel Lewis' health and removing to the upcountry he shortly thereafter "passed into the larger life."

Colonel Lewis' death threw the whole of the responsibility for the State's manufactory of arms on Charles Dick, and that, too, at a time when clouds innumerable darkened the horizon, and patriot that he was he shouldered the burden and by his execution of the trust writ large his name in this great State's roll of the faithful. For some time before this Mr. Dick had held a commission as "director" of the manufactory, but the exact date of his appointment to that position has not been discovered. Fortunate indeed it is for the student of the State's history that even so short a series of his letters has been preserved.

There must have been numbers of these documents covering the entire period of the existence of the work, there now remain only about twenty-five, the first bearing date Sept. 5, 1780, and the last, Dec. 10, 1782. Charles Dick's letters are rich not only in their revelation of detail relating to the gun factory but rich as well in their revelation of a personality. They are indeed business letters but they are not modeled on the pattern of that modern offensive document which is as "hard as nails" with its several parts so successfully constructed that when the "business sense spot" on the brain is touched these puzzle-picture parts jump into place completely obscuring every particle of personality (if indeed there is any) possessed by the "operator."

Not so Mr. Dick; what Mr. Dick really thought and really felt, that Mr. Dick dared to write. One is conscious in studying this brief series of documents of dealing with a human being. Absolutely fearless, honest and frank, very direct, he takes to task any one whose faults had affected the public; he does not offensively call names, that would have been beneath the dignity of so large a man, but in telling facts there is no rounding off of sharp truths, no attempt to soften merited rebuke. But his criticisms are essentially just. This man must have been "general efficiency" in compact form.

These letters reveal the fact of the tremendous effort Mr. Dick made to run the institution with almost no financial aid from the State. He staked his personal credit--he gave his word that the State would perform its obligations, and he held together a few men--sometimes more, sometimes less--on his personal word and got the most necessary part of the work done. The minutest detail received his most careful attention, and the burden of the large public duty he bore unflinchingly and to the bitter end of having to petition the House of Delegates that they might devise some method for his relief by which he could draw the very inadequate sum appropriated as a salary for him by the assembly, because in making up the list of civil officers of government for the appropriation law of 1782, his name had been omitted (Appendix II).

After a final letter of Mr. Dick's in December, 1782, making proposals for rehabilitating the great work, the manufactory of arms at Fredericksburg passed out of existence. Not so, Mr. Dick, however, for in succeeding years we find him filling various local offices of trust and working with his fellow citizens for the building up of Fredericksburg. In May, 1783, the assembly of Virginia enacted a law by which the gun factory and the public lands at Fredericksburg were vested in certain trustees, for the purposes of founding an academy for the education of youth.3

Appendix 8

[Virginia State Library, Executive Papers January 23, 1781]

Colo Fielding Lewis and Chas Dick were appointed by the Convention in 1775 Commissioners to Form, Establish and Conduct a Manufactory of Small Arms at Fredericksburg without any salary annex'd, as it was unknown the Troubles they might be at.

The first year being 1776. They accomplished the same after much Trouble and Attention, in putting the Factory on an extraordinary good footing; for which the Honble House allow'd them 10/ pr Day each; then equal to Gold or Silver amounting for the year 1776 to Cash £182:10:0 although they thought it not adequate to their Services they acquiesced. For the year 1777 they were allowed the same, and as the money had received no great Depreciation they said nothing.

The year 1778 they were allow'd £300 each, from which deducting the Depreciation as settled by Congress amounts only to £54:18:0

The year 1779 allow'd £1000 each, only worth 43:0:0

We having done the Business effectually with the greatest Dilligence and Integrity, to the great Benefit of the Public, we think it very hard to suffer so much, as it has not been in our power to make a bargain for Ourselves. We hope the Honble House will at least take our Services for these last two years into consideration and grant us a full Recompense.

The Subscriber his whole Time being taken up in that Service only has greatly injured him.

Chas. Dick

APPENDIX 9

[Virginia State Library, Executive Papers July 1785]

Sir

Having in consequence of an agreement entered into with the late Colo Fielding Lewis, in the year 1776, built a house on the Gun Factory Lot at Fredericksburg for the reception of the publick arms and ammunition, and having been deprived of the advantage of a final settlement with that gentleman by his removal to a distance from this place sometime before his death, we have been hitherto unable to obtain that compensation four (sic) our labour and expence to which we conceive we are justly intitled. Under these circumstances we hope to be excused for the liberty we now take in troubling your Excellency on this occasion, from whom we have the greater expectations as this work was commenced during your former administration and you may perhaps recollect something of the instructions which were given concerning it.

As Colo Lewis had transacted much business for the publick we could not doubt but that in this instance he was properly authorized and with this belief we readily undertook the work but having frequently experienced his scrupulous exactness in the observance of his contracts we thought even the usual precaution of a written agreement unnecessary relying on a few parole stipulations which we do not hesitate to say were all performed on our parts. This being the case we hope the omission occasioned by our confidence in the public agent, will not now operate to our prejudice. Every point necessary to the settlement of the account may still be ascertained of that the house was built cannot be doubted; if the charge is thought exhorbitant the opinion of men conversant in business of this kind we suppose would be satisfactory this being determined the balance due us will appear from the account we herewith take the liberty of transmitting and which we make no doubt will be corroborated by the one stated by Colo Lewis against the publick.

The sums which we now claim when considered in its different relationship makes very different impressions when it respects the publick it may perhaps appear trifling but when it relates to those whose chief support depends on their own industry and labour (a great proportion of which has been devoted in its acquisition) it becomes matter of very serious consideration not only to those who are immediately interested but to every individual who is possessed of only a common share of benevolence, we are persuaded from your unremitted attention of the general happiness of the community that you will also condescend to look down with attention to that of individuals which is so intimately connected wt it. And having considered our claim, we only request such relief as your excellency shall think we are in justice intitled to --and that your time may be no longer withdrawn from matters of more publick moment we beg leave to subscribe ourselves with the most perfect esteem and respect your excellenys

Most obt Hl Sers

Rd Brooke

James Tutt

Fredericksburg 1s July 1785

[Endorsed] His Excellency Patrick Henry, Esqr.

Dr The State of Virginia to Mesrs Brooke & Tutt for building a Magazine on the Gun Factory Lot at Fredericksburg by the direction Col Fielding Lewis

1776 Novr

To building a wall of Stone rated as brick work at

50 pr thousand which takes 152431 bricks 381: 6:6

To 2 outer dll doors and doors frames case 3: 0:0

To 1 staircase & Scantling 3: 0:0

To 3951 feet of scantling for roof window frames

& centers @ £8 pr thousand 31:13:0

To making 7 window frames @ 7/6 2:12:6

To 128 feet Cornice @ 1/3 8: 0:0

To 68 sash lights @ /9 2:11:0

To framing a hiped roof 9: 2:6

To shingling & planking 14 squares @ 11/ 7:14:0

To three pair hooks let into the wall for hanging doors 0:18:0

To 36000 feet of plank @ £6 21:12:0

To 10000 cypress shingles @ 20/ 10: 0: 0

To 11000 8d @ 24/ 13: 4: 0

To 8 window shutters & for hanging do @, 5/ 2: 0: 0

To underpinning the Storehouse & Coal House shed

for the Gun factory 5:12: 6

To 6 11 large nails 0: 5: 9

To framing 7 square of Centers @ 10/ 3:10: 0

To flooring the upper story 2: 0: 0

----------

£508: 1:9

1780 March 28. To balance as pr cona 431:16 :6 1/4

To interest on Do

[Endorsed] Account Brooke & Tutt with State of Virginia

1777 June 24 By Cash of Colo Lewis in paper money

@ £25 @ 2 ½ for 1 10: 0: 0

Augt 6 By Do of Do in Do £51 @ 3 for 1 17: 0: 0

1779 Novr 22 By Do of Do in Do £500 @ 6 for 1 33: 6: 8

179 Novr 22 By Do of Do in Do £500 @ 36 for 1 13: 7: 9 1/4

1780 March 28 By Do of Do in Do £102 @ 50 for 1 2: 0: 9 1/2

Balance due 431 :16 :6 1/4

-----------------

508: 1: 9

Erros Exd

Rd Brooke,

James Tutt.

APPENDIX 10

[Virginia State Library, Executive Papers February 1781]

February the 9th 1781

Dr. Sir

I expected to have received by Mr. Dick the money I have advanced for the public Gun factory at Fredericksburg for which he had a warrant on the Treasury, no man is a better judge of the loss I must at my rate sustain by not receiving my money than you, and most part of it was advanced as early as July and without such advance the factory must have been discontinued, as no money could be had at the Treasury or so little that business must have suffered greatly; had I suffered that factory to have stoped I know the public would have condemned me for it alltho' I should not have been blameable as the cause would have been the want of money. You may remember that I was desired to borrow all the money I could for the use of the State. I think I promised between Thirty and Forty Thousand pounds, seven Thousand of which I lent the State being all that I had at that time on hand. By these advances I have distressed myself greatly and at this time am not able to pay the collector my taxes and continue my business in the usual manner. I shall be greatly obliged to you to send me the Money by Mr. James Maury who has the warrant; can it be expected that the State can be well served when its best Friends are used in the manner I have been treated

I am Sr Your most Obedt Servant,

Fielding Lewis.

To

Colo George Brooke,

Treasurer of the State of Virginia

------------------------------------------------------------

1Hening, XI., 71 et seq.

2 [none specified in article]

3Hening, XI., 204

History.LibraryPoint.org editor's note: additional spacing has been added to facilitate readability. Those wishing to consult the original article should see:

"Fredericksburg in Revolutionary Days: Part III"

Article Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1916293