“I will honour Christmas in my heart, and try to keep it all the year. I will live in the Past, the Present, and the Future. The Spirits of all Three shall strive within me. I will not shut out the lessons that they teach.”

― Charles Dickens, A Christmas Carol

Charles Dickens was one of the most celebrated and influential novelists of the 19th century. His characters, literary devices, and plot elements were so successful they weigh heavily on the minds of writers and readers even today. Who hasn’t called a particularly unlikable or unsympathetic person “a Scrooge” at some point in their lives? Yet A Christmas Carol has an even wider influence on how our culture celebrates the Christmas season. The concepts of charity, gift-giving, and even a “white Christmas” are rooted in the literary imagination of Charles Dickens. Looking back through history, we can see how his distinct childhood influenced one of his most beloved stories―and Christmas as we recognize it today.

The Childhood of Dickens and the “White Christmas”

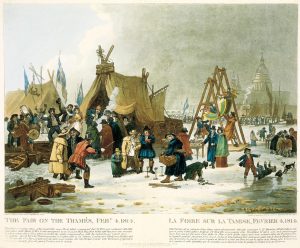

The dream of a “white Christmas”―children sledding and snowmen being built from endless white fields of snow―is so deeply entrenched in popular culture that it is difficult to imagine a time without it. But the distinct childhood experience of Charles Dickens is a large part of why this nostalgic imagery has become part of the Christmas season. Born in 1812, Dickens’ childhood Christmas seasons took place during one of the coldest decades in British history. In an average year in the UK, heavy snow in December is quite rare; heavy snowfall typically occurs from January to March. The 1810s were quite different. In 1814, it was so cold the River Thames froze over, and the ice was so solid that people had elaborate “frost fairs” that included walking an elephant across the river! The Little Ice Age was particularly chilling during Dickens’ early childhood and only ended in 1850, creating an unbreakable mental association of Christmas with snow and frost in his mind.

The unhappy times of Dickens’ childhood bit deeper than any winter cold and left an even greater mark on his young mind than the white Christmases of the 1810s. Dickens was one of eight children born to John and Elizabeth Dickens. His family didn’t have the money to ensure a good education for all their children, and young Charles was passed over in favor of his sister Fanny, who was sent to a music academy. Dickens would later be forced into work at the age of 12 and isolated from his family when his father was sent to debtors' prison. Although his father was eventually able to repay his debts with an inheritance he received, the unhappy months Charles worked in a blacking factory were the worst time of Dickens’ life. The experience of factory work influenced the many depictions of children isolated from their families, including lonely young Scrooge. Likewise, his mother’s insistence that he stay working in the factory after his father’s release colored the many cruel adults in his stories, such as the icy older Scrooge. Although his father won the argument with her and managed to get two more years of schooling for Charles, his son would never forget the exploitation of children and the sadness of the working class he was exposed to during his youth.

Three Ghosts to the Rescue

Although one would think he was destined to write A Christmas Carol because of his childhood experiences, the path that led to Dickens writing his classic tale was as much one of circumstance and luck. Long after his time in the blacking factory, Dickens was on the precipice of poverty in 1843. His literary career ran hot and cold, alternating between financial successes, such as The Old Curiosity Shop, and money losers, such as Martin Chuzzlewit. His financial situation was worsened by having to provide for a large family and overspending on a recent tour of America. Dickens needed a lot of money and a smashing success as quickly as possible. Even as he fell under financial pressure, Dickens never lost his affinity for the poor and tried to bring attention to the plight of the less fortunate. On October 5, 1843, Dickens gave a speech in Manchester for the benefit of the Manchester Athenaeum, a society that promoted art and education to the working classes. He was motivated by both his unhappy childhood memories and by the ravages of poverty he had seen a month earlier at the Samuel Starey’s Field Land Ragged School, a place for most impoverished children in London’s slums. Addressing the people of Manchester on that day and urging educational reform for the betterment of the poor, Dickens realized that the best way to reach a wide audience would be to publish a vivid story about the Christmas season.

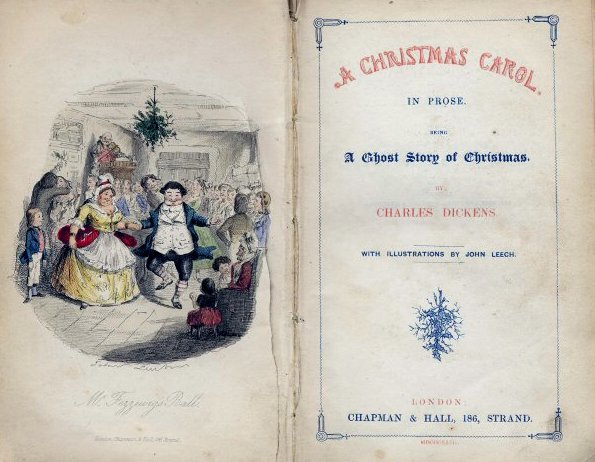

When it came time to write A Christmas Carol, Dickens made blazing progress. He completed the entire novella in only six weeks, sped along by the vivid memories of his childhood and the people he had encountered. Getting the story published proved more difficult than writing it. Dickens’ publishers, Chapman & Hall, had lost faith in him after Martin Chuzzlewit’s underperformance. They refused to pay the full cost of publishing A Christmas Carol, forcing Dickens to pay the rest himself. The cost of printing the novella was increased by changes Dickens wanted; he felt that the first printing looked drab and uninviting and chose a more expensive red cloth binding with gilt-edged pages for the final product. The book was a top seller in 1843, but the expenses of paying for its publication and its expensive binding meant that Dickens did not generate much income from it. Profits were further hurt by a cheap pirated edition released in 1844 titled “Christmas Ghost Story.” Although Dickens won his lawsuit against the publishers, he could not claim any money for his legal victory because the rival publisher filed for bankruptcy.

A Sea Change in Christmastime Cheer

The real success of A Christmas Carol for Dickens would be measured by decades, not months, and by its influence on the popular perception of Christmas in Britain and around the world. Stage productions of A Christmas Carol started being performed almost immediately after its publication. One version approved by Dickens appeared as early as February 5, 1844! But what truly cemented the novella into the public's imagination were the numerous readings Dickens performed of it from 1853 until his death. His performances had originally been for charity, but, in 1858, he started doing public readings of the novella for profit. Dickens was the rare writer who possessed a deep gift for theatrical presentation; he could keep a mass audience riveted for a 90-minute solo performance. Over the course of his lifetime, Dickens constantly edited and annotated the version of A Christmas Carol that he performed, modifying it to increase its impact on the audience. Dickens’ vivid, heartfelt readings of the story made it the favorite of all of his works for public performance, allowing him to make $140,000 on a US tour from 1867 to 1868. The once-underperforming novella had become the most enduring and lucrative thing Dickens had ever published.

As the story’s roots burrowed deep into Victorian popular culture, it began to alter the very nature of Christmas festivities in Britain. There was a long tradition of Christmas celebration in the United Kingdom, but it was centered around feasting, drinking, and caroling rather than giving gifts as a symbol of charity. The long “month of Christmas” that extended from December 6 (St. Nicholas Day) to January 6 (Twelfth Night) had been largely phased out by the early 19th century. The extended holiday was a victim of the population’s shift from rural to urban employment and the need of manufacturers to keep their industrial workforce on the job as much as possible.

Dickens had one eye in the past and one eye in the future in reimagining Christmas. Scrooge’s “Humbug!” of Christmas was a blunt statement of the attitude of many employers of his time; Fezziwig’s elaborate holiday celebration during young Scrooge's apprenticeship was a thing of the past. Dickens created in Scrooge a figure so ruthless, so lacking in charity, that he would deny his loyal employee Bob Cratchit even a single day off, marking Scrooge as a symbol of everything he hated about what industrialization had done to the British character.

Changing the focus of Christmas from being a month of merrymaking to a holiday about the importance of giving and charity had the effect of greatly romanticizing it. The spirit of giving and being thoughtful to one’s loved ones was connected to another 19th-century invention, the Christmas card. As A Christmas Carol began to steadily gain influence in the British imagination, Dickens himself became heavily associated with the holiday and its traditions, becoming “Father Christmas” in the popular imagination. Although Queen Victoria and Prince Albert brought the first Christmas tree into England, it still seemed like a foreign concept until Dickens made it as “English” as any other tradition with the story “A Christmas Tree”. Dickens was so strongly connected with the concept of Christmas that he could make a German tradition seem like it had been in Britain forever through his writing.

To children, traditions seem like they are set in stone, as if a Christmas tree, presents on the 25th of December, and the concept of a single day of giving have been there for thousands of years. So many of these things were not immutable and ancient, but the specific choices of one man’s story and how it has lived on in people’s minds and hearts over the decades. To learn about how we celebrate Christmas and how we see it is to learn the history of literature and the career of Charles Dickens. So many our traditions and mental associations date back to the tale of Ebenezer Scrooge and the three ghosts who haunted him. And, though he did not invent it, there is one last thing Dickens popularized through the story; the greeting, “Merry Christmas!”

Source List

The Little Ice Age and Weather in the UK

How Dickens Made Christmas White

https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20181217-how-dickens-made-white-christmas-a-myth

The Curious Story of River Thames’ Frost Fairs

https://www.thamesleisure.co.uk/the-curious-story-of-river-thames-frost-fairs/

Little Ice Age

https://www.britannica.com/science/Little-Ice-Age

Childhood of Charles Dickens

The Childhood of Charles Dickens

https://www.charlesdickensinfo.com/life/childhood/

Dickens and the Blacking Factory

https://www.williamlanday.com/2010/01/04/dickens-and-the-blacking-factory/

Charles Dickens, British Novelist

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Charles-Dickens-British-novelist

Charles Dickens Biography

https://www.notablebiographies.com/De-Du/Dickens-Charles.html

Writing A Christmas Carol

Charles Dickens Wrote “A Christmas Carol” in Only Six Weeks

https://www.biography.com/news/charles-dickens-a-christmas-carol#:~:text=Dickens%20began%20writing%20A%20Christmas,him%20craft%20a%20stronger%20story

Why Charles Dickens Wrote “A Christmas Carol”

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/why-charles-dickens-wrote-christmas-carol-180961507/

Manchester Athenaeum

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Manchester_Athenaeum

Dickens and “A Christmas Carol”

https://medium.com/@tudorscribe/did-charles-dickens-write-a-christmas-carol-for-the-money-604b46831981

A Christmas Carol: Social Influences

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Christmas_Carol#Social_influences

A Christmas Carol Trivia

https://www.charlesdickensinfo.com/christmas-carol/trivia/

Pirating Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol in the 1840s

https://daily.jstor.org/pirating-charles-dickens-a-christmas-carol-in-the-1840s/

Public Readings and Theatrical Productions

The Adelphi Theatre Calendar

https://www.umass.edu/AdelphiTheatreCalendar/img005f.htm

Adaptation of A Christmas Carol for public readings

https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/adaptation-of-a-christmas-carol-for-public-readings

Charles Dickens Amateur Theatricals

https://www.charlesdickenspage.com/charles-dickens-on-stage.html

Charles Dickens Once Gave an Epic Reading of “A Christmas Carol” in Boston

https://www.boston.com/news/history/2017/12/15/when-charles-dickens-read-a-christmas-carol-in-boston

Adaptations

https://dickens.ucsc.edu/resources/teachers/carol/adaptations.html

Older Celebrations of Christmas

A Georgian Christmas

https://www.historic-uk.com/CultureUK/A-Georgian-Christmas/

Newer Traditions and Christmas Cards

The History of the Christmas Card

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/history-christmas-card-180957487/

Where Did Christmas Trees Come From?

https://www.townandcountrymag.com/society/tradition/a25619292/queen-victoria-prince-albert-christmas-tree-holiday-tradition/

Merry Christmas and Happy Christmas

https://www.whychristmas.com/customs/merrychristmas.shtml