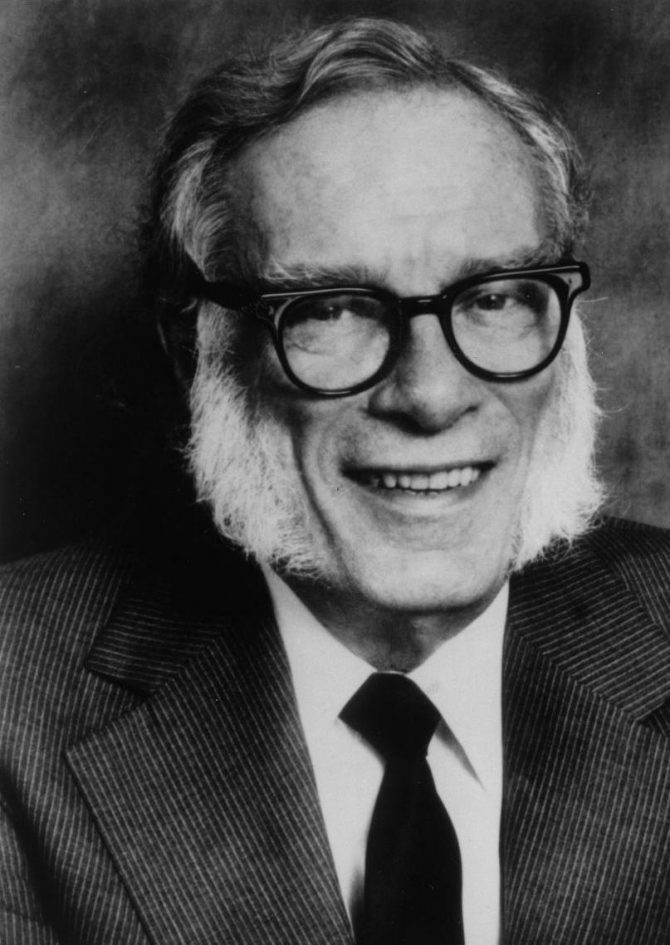

One of the great science fiction authors of both the Golden and Silver ages, Isaac Asimov is remembered as much for his innovative use of robotics and social science in sci-fi writing as he is for his “hard science” background and prolific output. Asimov’s concepts, such as the Three Laws of Robotics and that of a vast, disconnected empire of planets, were vastly influential in their time and retain their appeal to both science fiction writers and fans today. Asimov’s deep scientific knowledge and vivid imagination make him one of the great writers of the 20th century. This is an exploration of Asimov’s wonderful career as a writer and some of the essential titles he wrote that every science fiction fan should read.

Brilliant Dawn: Beginning Asimov’s Career

Born on January 2, 1920, in Soviet Russia, Asimov’s intellectual brilliance was apparent at an early age. His family immigrated to New York City when he was a toddler, and he began to excel in learning before his formal schooling began, teaching himself to read at the age of five. Once he began school, he was such an excellent student that he was able to skip several grades and graduated high school at 15. In his younger days, he frequently read the science fiction magazines and comics sold in his family’s candy stores in spite of his father’s disapproval. Despite this early interest, the beginning of Asimov’s official career as a published author would have to wait until his graduation from the University Extension of Columbia College in 1939.

Asimov began writing short stories in 1937, while he was still in undergraduate school. His first short story, “Cosmic Corkscrew,” took until 1938 to finish, and he then visited the offices of magazine Astounding Science Fiction to personally pitch it to editor John W. Campbell. Although Campbell did not publish the story in Astounding, he encouraged Asimov to continue his efforts, and Asimov would eventually get his third story, “Marooned Off Vesta,” published in Amazing Stories magazine in 1939. Asimov would refine his writing technique over numerous short stories published in pulp magazines until he created his landmark short story “Nightfall” in 1941. A story about the coming of darkness to a planet normally illuminated by sunlight at all times, “Nightfall” explored both the science of a world far different from Earth and the psychological effects of scientific and environmental change on the populace. These themes would influence another short story that Asimov would publish the following year, one that would begin one of his greatest works.

Enter the Foundation

In May 1942, “Foundation,” the short story that would begin Asimov’s critically hailed Foundation series, was published in Astounding. This first story of the series takes place in the decline of the Galactic Empire, as a once-mighty institution splinters and falls into chaos. It details the political intrigues taking place on the colony of Terminus as it attempts to maintain its independence from the petty kingdoms emerging from the declining Empire. Late in the story, the colony’s mayor, Salvor Hardin, makes a shocking discovery: the Terminus colony exists to be the home of a galactic Foundation that would bring civilization back to the former empire. “Foundation” was a major success with readers and critics, and Asimov would publish many other short stories set in this universe, taking place at various points between the fall of the Galactic Empire and the rise of the Second Empire. Other short stories in the Foundation series dealt with diverse subject matters such as the establishment of the Foundation’s official religion (“The Big and the Little”), a war between the Foundation and the remnants of the Empire (“Dead Hand”), and the emergence of the villainous telepathic Mule and the discovery of a mysterious second Foundation.

Asimov would continue publishing the Foundation short stories in Astounding for eight years before editing them into the three Foundation novels. 1951 saw the publication of Foundation, followed by Foundation and Empire in 1952 and Second Foundation in 1953. Many aspects of the novels would prove a major influence on later science fiction. The Mule, a dangerous enemy to the Foundation in the second and third novels, anticipates the Emperor of Star Wars with his ability to incite emotional tumult and his mysterious nature. Mathematician Hari Seldon, who created the Foundation with his concept of “psychohistory,” has proven influential in real-world studies through his incorporation of the “uncertainty principle” into social science. Foundation would retain its influence and readership over the decades, inspiring Asimov to create four other entries in the series: Foundation’s Edge (1982), Foundation and Earth (1986), Prelude to Foundation (1988), and Forward the Foundation (1993). The series was so critically acclaimed that it went on to win the only Hugo award ever for “Best All-Time Series” over other hallmarks of science fiction such as Heinlein’s Future History and E.E. “Doc” Smith’s Lensman series. Popular though the Foundation series was, adapting it proved difficult because of the high cost and complexity, forcing its fans to wait until the “prestige TV” era, when it would become adapted into a series by Apple TV+.

Three-Law Syndrome: The Origin of Asimov’s Robots

As influential as the Foundation novels are, Asimov’s Robot stories are perhaps even more crucial to the development of science fiction. Asimov’s first Robot stories were published in between 1940 and 1950 in Super Science Stories and Astounding Science Fiction in between 1940 and 1950. Although Asimov did not coin the term “robot”, he did invent the Three Laws of Robotics, which stipulated:

- A robot may not injure a human being, or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

- A robot must obey orders given to it by human beings except where such orders come into conflict with the First Law.

- A robot must preserve its own existence unless self-preservation conflicts with the First or Second Law.

The first book in the Robot series was 1950’s I, Robot, a compilation of Asimov’s short stories published with new wraparound material, similar to the Foundation novel. Influenced by an earlier short story by Eando Binder, Asimov’s short stories strove to break free of the “evil metal man” clichés that plagued sci-fi writing about robots at the time. The stories in I, Robot focused on robots that were friends, assistants, and rivals to humans, but whose lives and psychology were complex and three-dimensional. Asimov explored the logical contradictions of the Three Laws necessary to the mental operations of the robots and the nature of a robot’s positronic brain in the stories as well.

Asimov’s further entries in the Robot series changed from the short story format to a novel-length narrative. The second Robot book, 1954’s The Caves of Steel, is a detective story that introduces the characters of Elijah Baley and R. Daneel Olivaw, a robot detective. The story deals with the culture clash between Earth native Baley and “Spacer”-designed robot Olivaw as they work together to solve a murder and prevent a diplomatic crisis that could cause the annihilation of Earth. Baley’s Earth is an overpopulated world where virtually the entire population lives and commutes under gigantic interior structures, and robots are strictly regulated, whereas the Spacer worlds where Olivaw was designed are sparsely populated, rural, and have robots perform many important duties.

After the publication of The Caves of Steel, Baley and Olivaw would rapidly become favorite protagonists of both Asimov and his readers. Baley and Olivaw would next appear in The Naked Sun, another murder mystery. This one was set on the Spacer world of Solaria, a place so sparsely populated that the wealthy human colonists must rely on robots not only for specific tasks, but for most “human” interaction. Olivaw and Baley must discover whether the man responsible for operating the colony’s birthing center was murdered by his wife Gladia or by a robot--in spite of the Three Laws! As with the Foundation series, Asimov would continue the Robot series several decades later with The Robots of Dawn, ultimately fusing it to the Foundation series with Robots and Empire, a book that covered the transition between the Milky Way Galaxy setting of the Robot books and the later Galactic Empire. Robots and Empire also serves as a final adventure for R. Daneel Olivaw, as it takes place centuries after the death of his human partner.

A series-length adaptation of the Olivaw stories has never been made. The memorable 1964 episode of The Outer Limits titled “I, Robot” (and its 1995 remake) are both based on the Eando Binder short story rather than Asimov’s novel. Although both versions are directed in an “Asimov-esque” fashion and even make note of Asimov’s Three Laws in explaining the behavior of the robot, neither features Olivaw or Baley. An attempt in the late 1970s was made to create a film of Asimov’s I, Robot, but it was considered unfilmable given budgets of the time, and only Harlan Ellison’s screenplay for the prospective film remains. The BBC produced several Asimov adaptations as part of its science fiction anthologies, but only an adaptation of “Little Lost Robot” made as an Out of This World episode survived BBC’s old practice of wiping its tapes. In 2004, 20th Century Fox produced an I, Robot film as a Will Smith vehicle, but it was based on an unrelated spec script called “Hardwired” and had no direct ties to Asimov’s work. The adventures of Olivaw and Baley have yet to be truly realized on screen, as does the brilliance of Asimov’s robot characterizations.

A Final Word

Asimov’s gifts to the genre of science fiction are many. Through short stories and novels, he shaped sci-fi from the early Golden Age “space voyage” narratives to ambitious sagas about the development of artificial intelligence and the rise and fall of solar civilizations. Few writers retain their relevance over the course of a career spanning many decades, and it can be rare to have even one successful work. Asimov had dozens, and his lifetime is an inspiration to science fiction fans of all generations. Can humanity equal his robotic creations and visions of space travel in real life, or will we fall short of his grand adventures?

For all of Isaac Asimov's books in our catalog, go here.