The Rappahannock River and the surrounding forests provided rich land and plentiful game for the American Indians who lived here before the colonists arrived. Some of the tribes still live in and around the Rappahannock region. The Patawomeck,, opens a new window Rappahannock,, opens a new window Mattaponi,, opens a new window and Pamunkey, opens a new window all live in this area, and their people tell rich histories through their oral traditions and at their cultural centers. The struggles of these tribes to regain their ancestral lands and gain recognition from state and federal governments has been difficult and, in some cases, is ongoing. Read on for a little of the history of these four tribes, from pre-colonial times to the modern day.

The Patawomeck, Who First Watched the River

The Patawomeck tribe, from whose name comes the Potomac River, have their cultural center in Stafford County, opens a new window in Northern Virginia. The Patawomeck were part of the Powhatan Confederation, opens a new window, a large group of Algonquian peoples that encountered the early colonists at Jamestown. Because they lived relatively far from the Jamestown colony, the Patawomeck had a unique position in the Confederation in 1609. The Patawomeck strive to preserve their culture in modern times and have launched an effort to restore the use of the Patawomeck language, opens a new window.

The Patawomeck recently opened a museum and cultural center, opens a new window in southern Stafford County, also within easy driving distances of downtown Fredericksburg. Visitors can see important artifacts, opens a new window from Patawomeck history on self-guided tours. The museum also offers regular events and the ability to book school, homeschool, and field trips for other groups online., opens a new window

The Rappahannock, Who Sought Their Old Lands

Another tribe from the Powhatan Confederation is the Rappahannock, who were treated poorly by the colonists during their first encounter in 1603, opens a new window. A captain (likely Samuel Mace, opens a new window) sailed up the Rappahannock River and befriended the weroance (chief) of the tribe, but later killed him and took 60 people from the tribe as captives back to England. The tribe became a target of the British settlers after it took part in the Indian Massacre of 1622, opens a new window, as the colonists gained a hunger for both vengeance and the tribe’s lands on the river. Forced to move several times by the government of the Virginia colony over the course of the 1600s, opens a new window, they managed to return to some of their original lands in King and Queen County, in Virginia's Middle Peninsula. Their cultural center is located there today, and they are still involved in efforts to recover ownership of their historic lands, opens a new window.

The Mattaponi, Who Fought Nathaniel Bacon

The Mattaponi, who live on a reservation in King William County, Virginia, opens a new window, part of Virginia's Middle Peninsula, were a core part of the Powhatan Confederation. Falsely accused of attacking British settlements by Nathaniel Bacon, they were attacked and driven from their lands during Bacon’s Rebellion, opens a new window. They recovered their lands with the Treaty of Middle Plantation, opens a new window in 1677 and have maintained the terms of the treaty (an annual tribute of game to the Governor of Virginia) for over 300 years, opens a new window. The Mattaponi are one of only two, opens a new window Virginia Indian tribes (the other being the Pamunkey) who managed to retain their reservation lands from the 1677 treaty. Long recognized by the state of Virginia, the reservation was much smaller than the ancestral Mattaponi lands, and the tribe still seeks to recover what was lost. In 2023, opens a new window, the Upper Mattaponi acquired 853 acres of their historic lands along the Mattaponi River, which they will maintain as coastal wetland habitats.

The Pamunkey, The First Federally Recognized Tribe in Virginia

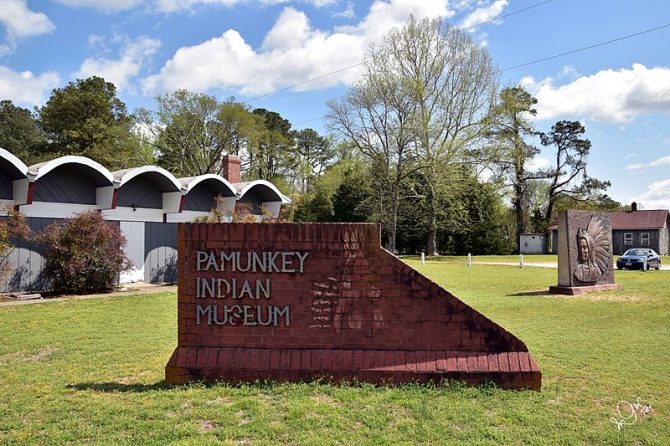

The other Virginia tribe to hold reservation land are the Pamunkey, who live on the border, opens a new window between King William County and New Kent County. The Pamunkey reservation is one of the oldest in the nation, dating back to 1646, opens a new window. Pamunkey interactions with the Virginia colonists date back to the time of Jamestown’s founding. In the winter of 1607, Opechancanough, opens a new window, weroance of the Pamunkey and brother of Powhatan, captured John Smith. He brought John Smith to Powhatan, and the Pamunkey began to offer food to the colonists. Powhatan's and the Pamunkey’s food donations kept the Jamestown colony alive over the first two winters. The Pamunkey keep many of their cultural traditions today, maintaining a pottery school, opens a new window and fish hatchery, opens a new window to allow their traditional ways of making pottery and fishing to continue.

Although Powhatan’s title is often given as “Chief Powhatan,” this is an overly simplified term for his position. Powhatan’s position in the Pamunkey language was called mamanatowick, a word which meant “chief of all chiefs.” The nature of Powhatan’s leadership was poorly understood by the colonists. Powhatan was believed to be not just a successful leader but a spiritually powerful man by the Pamunkey and other peoples of the Powhatan Confederacy; the Pamunkey believed that a person’s success in the physical world was linked to the strength of their spirit.1 Powhatan believed in the concept of a spiritual world linked to the physical through kinship bonds, and the capture and freeing of John Smith may have been an attempt to adopt him and create a kinship bond between the Powhatan and the British.

A Time of Strife: Bacon’s Rebellion

Neither John Smith nor the marriage of John Rolfe to Pocahontas helped the Pamunkey secure a better future from the colonial government. The Pamunkey, once a dominant tribe of the Powhatan Confederacy in 1607, were reduced to less than 200 warriors by 1676.1 Conflict between the Pamunkey and the colonial government had first erupted in 1609 when George Percy’s government demanded large amounts of food during a drought. The tribes felt slighted because the British had not provided them the support against their enemies that they felt they were owed by John Smith’s kinship bond. In response, they launched a series of attacks on the colonists and stopped providing them food. Many of the colonists were forced into the fort at Jamestown, and the period of famine and death there was known as the Starving Time, opens a new window. In vengeance, Lord De La Warr’s forces attacked villages of the Kecoughtan, Paspahegh, Chickahominy, and Warraskoyac tribes.2 The conflict ended by 1614 but left a legacy of anger and distrust between the colonists and the Powhatan tribes. Further wars in 1622-1626 and 1644-1646 would end with the Powhatan Confederacy losing much of its land and disbanding, opens a new window in 1646.

Their weakened position left the former Powhatan tribes vulnerable to the wrath of the colonists. In 1666, Virginia’s governor William Berkeley said, opens a new window that American Indians in the northern part of Virginia should be eliminated as “a great Terror and Example to all other Indians” and began to fund militias against them. At this same time, the Susquehannock, an Iroquian people originally from Pennsylvania, were forced southward into Maryland after their defeat by the Five Nations of the Iroquois.3 This forced more American Indian groups south into the Rappahannock and Northern Neck area. Tensions grew between the colonists and the displaced tribes until warriors of the Doeg tribe, opens a new window crossed the Potomac into Stafford County and stole pigs from Thomas Matthew, who had not paid them for their trade goods. Thomas Matthew then attacked the Doeg in Maryland, killing ten of them. The Doeg retaliated, opens a new window by killing Matthew’s son and two servants, and the violence that would lead to Bacon’s Rebellion began.

The conflict quickly grew and spiraled beyond the Doeg to other tribes. As the Stafford County militia tracked and killed the Doegs who had killed Matthew’s son and servants, another militia traveled north and attacked the Susquehannock, opens a new window in Maryland, mistaking them for the killers. Fourteen Susquehannocks were killed in the attack, and the tribe was blamed for several raids in Virginia and Maryland afterwards. The Susquehannock then sent a message to Governor Berkeley that they would cease attacks and “renew and confirme the ancient League of amety” with Virginia.3 Instead, both Berkeley and Bacon began to attack the Susquehannock across Virginia. Where Bacon split from Berkeley was in the end goal; Berkeley mainly wanted the Susquehannock gone, while Bacon wanted all Indians driven out of Virginia.

Bacon disobeyed Berkeley’s orders and brought his campaign to “ruin and extirpate all Indians in general” to the upper Pamunkey River. Once there, he massacred 50 Pamunkeys; the rest of the village was saved by the orders of their weroansqua Cockacoeske, who ordered everyone to flee into the swamp.1 Bacon then traveled westward to the territory of the Ocaaneechi, opens a new window, a Siouan-speaking tribe. After persuading them to attack the Susquehannock and bring back prisoners, his militia turned on them and massacred them. Bacon and his followers then returned to Jamestown, opens a new window, and the struggle shifted to a direct political clash with Berkeley. By the end, Jamestown was torched by Bacon’s forces, Bacon was dead from dysentery, and the other leaders of the rebellion were executed.

After Bacon’s Rebellion: The Quest for Recognition

Cockacoeske, who had proved pivotal in her tribe’s survival during Bacon’s Rebellion, also helped secure rights for American Indians after the conflict. She signed the Treaty of Middle Plantation, opens a new window in 1677, which allowed tribes to maintain their traditional homelands, bear arms, and hunt and fish as long as they maintained allegiance to the Crown and paid tribute. Of the tribes that signed the treaty, only the Mattaponi and Pamunkey still live on their original lands and pay the tribute. Other tribes gradually lost their land and cultural autonomy over the course of the colonial period and American independence. The Patawomeck (who did not sign the treaty) maintained a population in Stafford County, opens a new window around the site of their old village, but were not recognized by the state of Virginia for centuries. Their task was made even more difficult by Virginia’s Racial Integrity Act of 1924, opens a new window, which classified all nonwhite people as “colored” and serving to deny the recognition of American Indian tribes. The Rappahannock (who did sign the treaty) also faced great difficulty from it; they lost their original designation as “Indian” in records and were only recognized by the state in 1983, despite first incorporating, opens a new window in 1921.

Recent decades have seen considerable progress in Rappahannock-area tribes gaining state and national recognition. The Patawomecks were finally able to gain recognition from the State of Virginia in 2010, opens a new window, not through the Virginia Council on Indians, but through a bill sponsored by Bill Howell, Speaker of the House at the time. Efforts are currently underway for the Patawomeck to gain federal recognition via a bill, opens a new window sponsored by Abigail Spanberger, Jennifer Wexton, and Jen Kiggans. The Rappahannock gained recognition by the state in 1983, opens a new window, and from the federal government in 2018, opens a new window via Rob Wittman’s Thomasina Act. Legislation was required because the tribe had suffered the loss of their original documents from Virginia’s Racial Integrity Act and because the tribe did not have a reservation. Both the Mattaponi and Pamunkey have been recognized by the state of Virginia since the 1600s. The Upper Mattaponi, opens a new window, a band that did not live on the Mattaponi reservation, also gained federal recognition with the Thomasina Act. The Mattaponi on the reservation are still seeking, opens a new window federal recognition. The Pamunkey began their federal recognition petition in the 1980s and were only recognized by the federal government in 2015, opens a new window.

Federal and state recognition can bring useful benefits for American Indian tribes, which is why some have sought it for decades. Federal recognition means that the U.S. government grants an American Indian tribe a degree of sovereignty., opens a new window This allows the tribe to establish a tribal government, which can enter into agreements with the federal government in a similar manner that state governments do. Federally recognized tribes can also have their lands placed in trust, opens a new window to protect them from sale and lease and are allowed access to services provided by the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Recognition, opens a new window from the Commonwealth of Virginia provides a special relationship with the state government, granting the tribe mandatory consultation and protections for federal projects on tribal land. State-recognized tribes may also have a seat on the Virginia Indian Advisory Board,, opens a new window which reviews applications for other groups seeking tribal recognition. State recognition does not provide all the benefits of federal recognition. For example, tribes recognized by the Commonwealth of Virginia but not by the federal government are ineligible for benefits, such as NRCS tribal assistance., opens a new window

The tribes of our area have faced many challenges in the past but have striven to maintain their identities and traditions. In the 21st century, they seek to regain their historic lands, restore their languages, and seek additional recognition from the federal government. American Indians all over the nation strive for better futures, including the first peoples the Jamestown colonists encountered.

Sources

1Ethan A. Schmidt. “Cockacoeske, Weroansqua of the Pamunkeys, and Indian Resistance in Seventeenth-Century Virginia.” American Indian Quarterly, vol. 36, no. 3, 2012, pp. 288–317. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.5250/amerindiquar.36.3.0288, opens a new window. Accessed 15 Feb. 2024.

2Fausz, J. Frederick. “An ‘Abundance of Blood Shed on Both Sides’: England’s First Indian War, 1609-1614.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, vol. 98, no. 1, 1990, pp. 3–56. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4249117, opens a new window. Accessed 15 Feb. 2024.

3Rice, James D. “Bacon’s Rebellion in Indian Country.” The Journal of American History, vol. 101, no. 3, 2014, pp. 726–50. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/44286295, opens a new window. Accessed 15 Feb. 2024.