From the Greater Fredericksburg Tourism Partnership

INTRODUCTION

Fredericksburg is located at the falls of the Rappahannock River - the point where the flat, sandy, coastal plain meets the hilly, rocky piedmont to the west. This is where the river becomes unnavigable - rocky rapids and shallow waters make its channel impassable to vessels.

Fredericksburg is located at the falls of the Rappahannock River - the point where the flat, sandy, coastal plain meets the hilly, rocky piedmont to the west. This is where the river becomes unnavigable - rocky rapids and shallow waters make its channel impassable to vessels.

However, this is where the river has its maximum water power potential. The fall of the rapids over the piedmont creates a great amount of water power which can be harnessed to turn water wheels and turbines. The resulting energy can be used to run mill machinery or to create electrical energy.

Therefore, Fredericksburg has always been a favorable location for milling. The river provided valuable water power as well as an important transportation link for receiving raw materials and shipping finished products. Prior to the Civil War, most of the city's mills were owned and operated by local investors.

However, after the war, there was an influx of northern investment. Investors, realizing the industrial potential of the area, took over the existing mills and built new mills and factories along the power canal system of the Fredericksburg Water Power Company.

By the early 1900s, electrical power came into increased use in the region. Mills and factories were gradually converted to this more efficient form of energy. No longer was it necessary to locate industry on a waterway; electric lines could be strung almost anywhere. Slowly, Fredericksburg began to decline as an industrial center.

However, the river took on a new function at the turn of the 20th century - that of generating electrical energy. Several power plants were built on the canal system.

By the 1960s, it became impractical to generate electricity on a relatively small scale in Fredericksburg, and the last electric generating plant was closed. This was the final use of Rappahannock River water power in the city.

EMBREY DAM

The first dam was built near this site in 1855 by the Fredericksburg Water Power Company. The company purchased the Rappahannock Navigation Company canal system in the early 1850s and converted the system's primary function from transportation to water power. The water power company sold lots along the canal system and rented water power privileges usually by the horsepower.

The wooden crib dam stood about 60 feet upstream of the present-day Embrey Dam, diverting water into the main canal of the water power company. It furnished about 5,000 horsepower of water power which ran through the canal and raceways of the city.

The Embrey Dam was completed by the water power company in August of 1909. It was constructed of reinforced concrete and furnished about 8,000 horsepower of water power. The dam diverted water into the main canal until the early 1960s, when the last electric generating plant on the canal system was closed.

UPPER LEVEL MILLS

These mills were located on the upper raceway which ran along the western side of Caroline Street, opposite present-day Old Mill Park. They were powered by water from the Fredericksburg Water Power Company Canal.

Water was let into the canal by gates at the dam and flowed to the turning basin (where canal boats turned around after delivering their cargo). A raceway continued from the basin, running under Princess Anne Street to the milling area. There each mill had its own headrace extending from the main raceway.

Excelsior Mills was located near the Railroad Bridge, on Sophia Street.

Fredericksburg Paper Mill was located on the canal near the site of the present Water Purification Plant.

LOWER LEVEL MILLS

These mills were located on the lower raceway which ran along the eastern side of Caroline Street, from just below Lauck's Island, through present-day Old Mill Park. Water could be fed into the raceway in either of two ways.

It could be let in by a small dam at the raceway's genesis below Lauck's Island. The dam was built sometime prior to 1817 and rebuilt in 1907 by the Bridgewater Milling Corporation. The company controlled all of the water rights along the lower raceway at that time.

Alternately, water from the upper level raceway could be reused after powering the wheels and turbines of the upper level mills. Their tailraces led the water under Caroline Street and into the lower level raceway where it powered other mills. Apparently, this system was used during drought periods when there was not sufficient water reaching the dam of the lower raceway.

KENMORE AVENUE RACEWAY

The third component of the canal system was a raceway, historically called the "canal ditch," which branched off the main canal near the paper mill. The raceway ran around the west side of the city, following the mute of present-day Kenmore Avenue, and ended at Excelsior Mills on the east side of the railroad bridge. The raceway ran underground from a point near the railroad station before powering the water wheel of Excelsior Mills and emptying back into the river.

The paper mill and Excelsior Mills appear to have been the only enterprises powered by the raceway. It was filled in during the second quarter of the 20th century when unused, it became a public nuisance.

THE GRIST MILLS

During the 19th and early 20th century, Fredericksburg was home to several large commercial grist mills. These mills ground various grades of flour, meal and animal feeds on toll and for wholesale and retail distribution.

Wheat and corn were purchased from local farmers who hauled their grain by horse and wagon to the mills in Fredericksburg. Once ground, the finished products were shipped as far as New York City, Philadelphia, Baltimore and ports in South America. The mills also maintained salesrooms and offices in downtown Fredericksburg where they sold their products.

The flours and meals were sold in both wooden barrels and cloth bags. Some of the mills ran cooper shops on the premises where barrels were produced as needed.

THORNTON'S MILL

About 1720, Francis Thornton, Sr., erected a grist mill on the Rappahannock River in Fredericksburg, a short distance upstream of the present-day Falmouth bridge. Little is known about the mill, but it is said to be Fredericksburg's first milling enterprise.

In July 1783, Francis Thornton III appeared in Stafford County court. He had extended the mill's dam all the way across the river to the opposite bank, when James Hunter of Falmouth did the same upstream. This cut off valuable water power to Thornton's Mill.

Thornton argued that Hunter's dam diverted "the water out of its usual courses from your petitioner's mill, thereby rendering it but little value and making it necessary that your petitioner run his dam across the same to the bank on the other side:" The court ruled in Thornton's favor, finding that "no possible injury can arise to any person by [the dam's]ponding water" on the river.

In 1793, Francis Thorton III or IV advertised that he had a "mill seat" (mill site) to be let. He said that a substantial set of mills could be built on the site, for it "command[ed] the whole of the water of the river above the falls, which is sufficient, in the driest of season, to turn twenty pair of stones."

In July 1796 architect, designer, and naturalist Benjamin Henry Latrobe visited Thornton's Mill. Latrobe seemed to be quite impressed by the potential water power of the Rappahannock. He remarked that "The River tumbles over a ridge of Granite...The greatest, or most sudden fall is between Mr. Thornton's Mill and Tide Water."

RAPPAHANNOCK ELECTRIC LIGHT & POWER COMPANY

The Rappahannock Electric Light and Power Company was founded in 1887 by a group of local investors. The power plant was located in the old Knox sumac mill, in present-day Old Mill Park (see Knox's Mill).

Fifty horsepower of water power was allocated to run the dynamos of the electric generating plant.

The plant provided electricity for city street lights as well as power for homes, businesses, industry, and public buildings. On November 3, 1887, Fredericksburg was lighted for the first time with electricity.

By 1891, the company had been bought by the Ficklen family, owners of Bridgewater Mills. In 1901, a new plant was constructed on the lower raceway on the north side of the Falmouth Bridge in Fredericksburg. The two story, wood frame plant had two Westinghouse dynamos, turned by turbines in the plant's basement, which furnished power to customers 24 hours a day.

In 1907, the plant powered 2,000 incandescent lights and 10 arc lights, as well as providing 24 horsepower of energy for motors and 50 electric fans. That same year it boasted having more than ten miles of wiring.

The power company was later managed by Ellen Caskie London Ficklen, the wife of J. B. Ficklen, Jr., general manager and owner of the Bridgewater Mills. Mrs. Ficklen managed the Rappahannock Electric Light and Power Company from 1901 to 1923. She is said to have been the first woman in the United States to head a utility company.

In 1923, the Spotsylvania Power Company bought the Rappahannock Electric Light and Power Company, taking over its customers on its own lines.

Bridgewater Mills

"No single industry located in Fredericksburg has done so much toward carrying the name and fame of the city to all parts of the world as the Bridgewater Milling Corporation," remarked a local newspaper in 1907.

This mill gained international recognition when it won a diploma and silver medal for its display at the Paris Exposition of 1878. Bridgewater Mills also produced the first flour branded "family" in the United States.

The mill was owned and operated by Joseph B. Ficklen, a wealthy Falmouth resident. Ficklen's two sons, J. B. Ficklen, Jr., and W. F. Ficklen, both worked for the milling company. Both sons eventually became partners in the business.

The mill sat on the lower raceway, just south of the Falmouth Bridge in Fredericksburg. It had the capacity of producing about 160 barrels of flour and 400 bushels of meal per day in the late 19th century. While the mill originally employed burr stones, a roller system was installed in the 1880s. In 1884, about 110 horsepower of water power was required to run the mill.

While the original mill was built in 1822, it was continually expanded. When a fire severely damaged the structure in 1858, it was quickly rebuilt. By the late 19th century the milling complex consisted of a connected string of buildings including a flour mill, corn mill, warehouse, and grain elevator. Adjoining were cooper shops, stables, millers' houses and an office.

The mill produced ten grades of flour, "Ficklen's Superlative" being the best. It also ground corn meals and animal feeds.

In 1912, the mill was closed down and was used by the Rappahannock Electric Light and Power Company to house electric generating equipment. The flour mill was never reopened.

FREDERICKSBURG WOOD WORKING PLANT

One of the city's least known and shortest lived enterprises, the Fredericksburg Wood Working Plant, was built in 1896 adjacent to Bridgewater Mills. The Bridgewater Milling Company leased the wood working company the plot of land upon which the plant was built, as well as the use of 60 horsepower of energy from their water wheel.

The two-and-one-half story wood working plant was woodframed and iron clad. Planing and sawing was conducted on the first floor, planing on the second, and the third floor was used for storage. A kiln for drying wood stood adjacent to the structure.

The machinery was powered by a 150 foot belt connected to the water wheel of the Bridgewater Mills. The belt was housed in an underground "car power box" which connected the plant with the wheel house of Bridgewater Mills.

The wood working plant produced milled lumber and house trim and orders were shipped as far as New York City and Boston. In 1896, a local newspaper reported that the plant had "found ready sale for more than they can turn out, and have been compelled to turn down orders, being unable to fill them in time."

However, by 1904, both the Bridgewater Mills and the Fredericksburg Wood Working Plant were shut down. In 1907, the plant was offered for sale or rent in a local newspaper.

It does not appear that the plant was ever reopened.

KNOX'S MILLS

Robert T. and James S. Knox were the sons of Thomas F. Knox, a Fredericksburg merchant who ran a local shipping company. Knox also ran a grist mill which was situated on the lower raceway in present-day Old Mill Park.

After the Civil War, the sons took over the business, taking the name R. T. Knox & Brother, and in 1867 converted the old grist mill into a sumac and bone mill. The plant actually had three mills, two for processing sumac and one for grinding bone dust, used in making fertilizer.

In 1884, the factory had the capacity for producing about 1,000 tons of sumac per year. It was also manufacturing fertilizer, which was sold to local farmers.

Sumac grew in abundance around Fredericksburg and people could make money by collecting the leaves and selling them to local dealers. The sumac was either ground, to be used in the process of tanning leather, or extracted as a liquid, used in dyeing textiles. It appears that both processes were carried out at the mill. The mill burned in the late 1890s and was never rebuilt.

HOLLINGSWORTH'S MILL

This early 19th century mill was located on the lower raceway in present-day Old Mill Park, on or near the site of Knox's Mill. This may have been the same mill which Thomas F. Knox operated before the Civil War (see Knox's Mill) or may be an earlier mill on the same site.

The first known account of the mill is from August, 1807, when a local newspaper reported that high river waters resulting from heavy rains damaged the raceway which conveyed water to Hollingsworth's mill. At this time, it was operated by William Hollingsworth and a Mr. Cooch. Cooch and Hollingsworth operated a grist mill, Rappahannock Forge Mills, further upstream near Falmouth as early as 1802.

GERMANIA MILLS

This mill was located on the upper raceway, just a quarter mile from Bridgewater Mills. It was owned and operated by J. H. Myer and F. Brulle. Myer was a German who came to this country in 1846 and soon after settled in Fredericksburg. He ran the mill office and sales room on William Street. Brulle, a Prussian who came to Fredericksburg in about 1850, ran the mill.

The mill burned in 1876, but was immediately rebuilt. The new mill building was brick, four stories tall, and had a metal roof for fire protection. Eight runs of mill stones powered by three turbines had the capacity of producing 150 barrels of flour and 200 bushels of meal per day. Fifty horsepower of water power were required to run the mill.

In the late 1880s the mill's burr stones were supplemented with a new roller system. The rollers eventually replaced the mill stones completely.

In 1917, a reinforced concrete grain elevator was built adjacent to the mill. It had the capacity of holding 45,000 bushels of grain. The mill continued to operate into the first quarter of the 20th century.

CITY ELECTRIC LIGHT WORKS

This city-run electric light plant was located on the upper raceway, halfway between Washington Woolen Mills and Germania Mills. It was completed in 1901 by the City of Fredericksburg.

The city had contracted with the Rappahannock Electric Light and Power Company for lighting its streets, but eventually it was felt that the street lights could be maintained more economically and efficiently if the city had its own electric generating plant.

By 1919, the plant was closed.

WASHINGTON WOOLEN MILLS

On May 10 ,1860, the first water poured over the water wheel of the Washington Woolen Mills. The hugh iron wheel was fed by a headrace extending from the canal of the Fredericksburg Water Power Company.

The four story brick mill could produce up to 100,000 yards of woolen goods per year. On the day it opened, it had orders for $30,000 worth of merchandise.

In 1876, the mill was destroyed by fire, but was quickly rebuilt. By 1884, it was one of the city's leading industries, employing 30 or more people and producing about 120,000 pounds of wool per year.

A visitor to the mill in that year described the operation. "As we gaze at the rapid play of shuttles, and as we watch the work of spindles and of cards, our ears in the meantime almost deafened by the sounds produced."

In 1907, there were 45 looms and five sets of cording machines operating in the mill "all of the latest pattern, turning out goods that always [found] a ready sale in the markets of the world."

By 1909, a pants factory was added to the Fredericksburg complex which produced men's wool and flannel pants.

In August 1910, a fire blazed through the mill, sparing only the pants factory. Nearly 300 people worked for the company at this time, many of whom were put out of work. The woolen mill was never rebuilt, but the pants factory, which was powered by electricity, continued to operate for a number of years.

C. W. WILDER AND COMPANY SILK MILL

KLOTZ COMPANY

In August 1889, C.W. Wilder of New York and George F. Wheeler of Baltimore approached the Fredericksburg City Council. They offered to build a silk mill in the city, providing the City Council would grant them an acre of land upon which to build the factory and exempt the company from city taxes for a 10-year period.

In return, the men promised to build "a factory that would employ up to 200 girls and women from age 15 upward." The council agreed to the concessions and by June 1890 the mill was in operation.

The silk "throwing" mill wound or twisted raw silk into thread before it was sent to be woven by silk manufacturers. Imported primarily from Italy, the raw silk was first washed and dried, then spun by "the nimble fingers of the female operatives ...kept busy tying the delicate fibre when broken," and finally wound or "doubled" into skeins of thread.

The single-story brick mill was driven by 20 horsepower of water power. A cable attached to the mill's water wheel turned overhead shafts which powered the mill machinery. Later, a 25 horsepower steam engine was installed to supplement this system in times of drought. By 1919, the mill was operated entirely by electricity.

Five months after it opened, the mill employed 30 operatives. By 1897, it would employ up to 160 people, becoming one of the city's leading employers and bringing many workers to the area.

In 1900, the mill was sold to the Klotz Throwing Company, a large firm which operated silk throwing mills in Pennsylvania and Maryland. In 1934, a fire destroyed the Fredericksburg mill, putting 90 people out of work and ending Fredericksburg's days as a silk "throwing" city.

SPOTSYLVANIA POWER COMPANY POWER HOUSE NUMBER 1

/ EMBREY POWER PLANT

About 1910, entrepreneur Frank Jay Gould purchased the Fredericksburg Water Power Company. Soon after, he established the Spotsylvania Power Company and built Power House Number 1. The plant utilized the canal and dam of the old water power company, providing the city with "the lowest rates for electric lights, heat and power on the Atlantic Seaboard, from Maine to Florida."

The power house was constructed of reinforced concrete and steel. It was powered by water from an underground headrace extending from the water power company canal. Six electrically operated gates at the Embrey Dam controlled by switches at the power plant regulated the flow of water into the canal.

The water was first accumulated in storage silos and then forced downward onto turbines which turned dynamos. The dynamos could produce up to 3,000 kilowatts of electric current, carried to customers on overhead wires strung on reinforced concrete poles.

In 1923, the power company had 1,011 customers in Fredericksburg and 60 employees on the payroll. By 1926, it was serving 2000 customers in the city.

In April 1926, the Fredericksburg plants were sold to the Virginia Electric Power Company. In November of that year, a power line between Richmond and Fredericksburg was opened, connecting the plant with other areas served by VEPCO. This ensured the city adequate power in times of drought, while excess power could be carried to areas farther south in the company's system.

In the early 1960s, the Virginia Electric Power Company stopped operating the power house when the water level of the Rappahannock became too low to power the plant much of the year.

FREDERICKSBURG PAPER MILL

Established by a group of local investors, the paper mill was located on the south side of the Fredericksburg Water Power Company canal, near the site of the present-day city water purification plant.

When the mill started operation in December 1860, prospects for the new enterprise were good. One local newspaper reported, "Virginia newspapers will soon have the opportunity of purchasing a superior article for printing, without going North for their supplies."

The mill was powered by two water wheels which provided 60 horsepower of energy to run the machinery. In 1861, the mill was producing about 2,000 pounds of paper per day and employed 20 people.

During the Battle of Fredericksburg, the mill building was occupied by Union Troops and much of the mill's machinery and part of the building were destroyed. After the war, the mill was repaired and new machinery installed. However, the new owner, Levi A. Beardsley, soon sold the mill to the New York and Fredericksburg Cane Fibre Company. The firm shipped reed cane fiber from the Dismal Swamp near Norfolk.

The fiber was reduced to pulp and pressed into felt paper sheets used in roofing, and brown paper used for bag making.

On February 14, 1877, the mill was completely destroyed by fire accidentally set by an employee.

EXCELSIOR MILLS

Located on the east side of the railroad bridge in Fredericksburg, the Excelsior Mills were built in 1861 by John L. Marye. During Marye's time the mill was known as Marye's Mill.

After Marye's death in 1866, the mill changed ownership a number of times, in several instances falling into the hands of northern investors who hired local millers to run the operation. C. H. Pettit was one such miller, who worked at the mill since boyhood and went on to become a partner in the business. Pettit eventually became sole owner of the enterprise.

The mill consisted of two buildings, a wooden warehouse and a brick mill building connected by a single story, wooden passageway. It was powered by an overshot water wheel, fed by the raceway extending from the paper mill (see Kenmore Avenue raceway). Excess water was channeled around the wheel by way of a waste way which emptied back into the Rappahannock River.

In 1884, the mill had five runs of burr stones and the capacity of producing about 60 barrels of flour and 50 bushels of meal per day. Three years later, the burrs were replaced by a new roller system. By 1891, the operation had eight sets of rollers and one run of burr stones.

In 1909, the mill building was bought by the Fredericksburg Water Power Company. The company cut off the flow of water to the mill in order to increase the amount of water in the main canal for the new electric generating plant. In 1912, the mill building was vacant and by 1919, it disappeared from local maps.

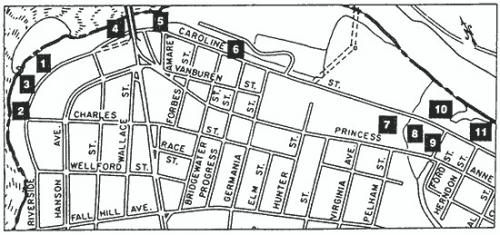

1. Indian Punch Bowl

2. Site of First Mill Thornton's Mill

3. 1907 Dam and Gates

4. Site of Rappahannock Electric Light & Power Co.

5. Bridgewater Mills Foundations(1822)

6. Knox Bone Mill & Sumac Mill Foundation

7. Ruins of Myers & Brulle's Germania Flour Mill

8. Foundation & Wheel Pit of City's Hydro DC Plant

9. Wheel Pit of Washington Woolen Mills

10. Plant of Spotsylvania Electric Co., later Vepco, and Embrey Power plant.

11. Portions of Klotz's Throwing Co. and C. W. Wilder and Co. Silk Mill

Brochure research and text by Peter Pockriss. Additional research information is on file at the Central Rappahannock Regional Library.